Life

THE ADVENT

We do not know when the Mukherjis came to Jayrambati. From two old documents it appears that sometime in the middle of 1669 a certain King of Vishnupur, named Sri Chaitanya Simha, gifted about six acres of land, free of all rents, to one Khelaram, a forefather of the Mukherjis, for the maintenance of his family and for carrying on the worship of Dharma. From this it appears that the Mukherjis had been worshippers of the deity even earlier and might have come to the village in that capacity. This was perhaps during the transitional period in the history of Bengal when Buddhism was being absorbed into Hinduism together with its deities of whom Dharma, under various names, was one. But once the Mukherjis had set their feet in the village, they became the family priests of the Hindus near about and thus gradually established the supremacy of Hinduism, owing to which Simhavahini, the Hindu deity, whom too the Mukherjis worshipped, became the presiding goddess.

The site occupied by the Holy Mother temple was perhaps the first place where the Mukherjis settled. This is borne out by the Siva image in black-stone which was found underground when the foundation for the temple was being dug. This must have once been worshipped by the Mukherjis. The Mother lived here till she was nine years old, and this was also the place which witnessed her marriage. ‘My marriage was celebrated in the old house,’ she recounted. ‘We shifted to the new house (which later fell to her brother Varada’s share) when I was nine years old— when the old house became too small.’ Ramachandra, a worthy descendant of the Mukherjis, whose tutelary deity was Rama, was respected at Jayrambati for his godliness, suavity of temper, and compassion for all. He married Shyamasundari Devi, daughter or Sri Haridas Mazumdar of Shihar. The wife, too, vied with her husband in the practice of virtue. Her purity, simplicity, and fortitude were the talk of the village. The Holy Mother Sri Sarada Devi was born of this pious couple. The few sentences which occasionally dropped from the Mother’s lips with regard to her parents go to show how virtuous they were and in what veneration she held them ‘My parents,’ she said,’ were very good. My father was a devout follower of Rama. He was very orthodox and would not accept any gift from people of other castes. How kind my mother was; how she would feed people, and how she took care of them! And how guileless she was!’ And she added, ‘My father liked smoking. But as he smoked, he was so simple and humble that he would address in a friendly way any passer-by who crossed his door, and would say, “Sit down, brother, and have a smoke.” And then he himself would fill up pipe after pipe for him Will the Lord be born where the parents are not self composed ?’ About her mother she said,’ My mother was Lakshmi (goddess of fortune) herself,. so to say. Throughout the year she would gather all sorts of things and keep them in order. She would say, “ My household is for God and His devotees…”. This household was, as it were, a part and parcel of her being. What pains did she not take to keep it in order!’

Ramachandra had three younger brothers—Trailokyanath, Ishwarchandra and Nilmadhav—all of whom lived together. This family was never prosperous and somehow made both ends meet with the little that was earned by farming and priesthood; and yet Ramachandra was unstinting in his charity, of which we shall have some proof in due course.

Once when Shyamasundari Devi was living with her father in the northern part of Shihar, she had occasion to sit in the dark beside a potter’s oven under a bel (bilva, aegle marmelos) tree. There suddenly issued a jingling sound from the direction of the oven, and a little girl came down from the branches of the tree. She laid her soft hands round Shyamasundari’s neck, whereupon she fell down unconscious. She had no idea how long she lay there thus. Her relatives came there searching for her and carried her home. On regaining consciousness she felt as though the little girl had entered her womb.

Ramachandra was then in Calcutta in search of some means of earning money for his family. The thought of his family’s poverty weighed heavily on his mind. One day, before he had decided to start for the city, he was engrossed in that thought. Then he fell asleep and dreamt that a little girl of golden complexion embraced him from behind by throwing her delicate arms round his neck. The incomparable beauty of the girl, as also her invaluable ornaments, at once marked her as out of the common run. Ramachandra was greatly surprised and asked, ‘Who are you, my child?’ The girl replied in the softest and sweetest of voices, ‘Here am I come to you.’ Ramachandra woke up and the conviction grew in him that the girl was none other than Lakshmi, the goddess of fortune, whose appearance implied that the time was auspicious for him to go out in quest of money. Accordingly he left for Calcutta. We do not know how far Ramachandra was successful in his quest. All that we know is that after returning home he heard what had happened to his wife, and, spiritually-minded as he himself was, he readily believed everything. Henceforth this holy Brahmin couple lived the purest of lives in expectation of the divine child. Ramachandra had the highest regard for his wife and never touched her person till the birth of the Holy Mother. Shyamasundari Devi was conscious of her unique fortune, and long after she said to Yogin-Ma,1 ‘How beautiful I looked when I was in the family way, how thick were my tresses, and how many pieces of cloth were presented to me during that time! ’

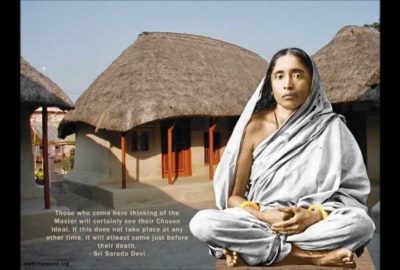

Gradually the time of confinement approached. Autumn had now passed, and it was the beginning of the month of Paush when winter had just set in. This was one of the happiest times in Bengal villages. The harvest was over and the granaries were full. The fields around again began to smile with the shooting forth of the summer crop. The new harvest festival had just been finished, and the little children were counting the days for the festival of the monthending1 when they would have a feast of cakes. The Christian world was eagerly waiting for the merry Christmas day. The Tantrikas were busy paying visits to the Kali temples, especially as such visits were thought to by very meritorious in that month. And it was the day of winter solstice when the longest night was over and the sun was beginning its northward course—the day on which the Hindu gods and goddesses wake up from their long slumber of six months. During such a time, a little after Thursday evening, on the 8th Paush (22nd December, 1853) when the night had spread her star-spangled cloth over the village of Jayrambati to lay it asleep after the day’s labour the blowing of conchshells from Ramachandra’s house announced the happy news of the advent of Sri Saradamani Devi. Soon an astrologer was called in and in accordance with the disposition of the stars and planets at the time, the child was ceremonially named Thakurmani. Her more popular name was, however, Saradamani.2

Sarada was the first child of her parents. She was followed by a sister named Kadambini and then by five brothers named Prasannakumar, Umeshchandra, Kalikumar,

Varadaprasad and Abhaycharan. Kadambini died childless soon after her marriage with Sudharam Chakravarty of Kokanda. Umesh, too, died before marriage at the age of eighteen or nineteen. Abhay died just after passing out of a medical school, leaving behind him a widow and a daughter, of whom we shall have much to say in future. The other brothers grew up and set up separate houses and reared their own families. Uncle1 Kali built his house south of the ancestral home. Uncle Varada’s house was to the north-west of uncle Kali’s. South-west of this house was the Kalu-gede (Kalu’s pond) mentioned earlier, which was used by the Mukherjis for cleaning the household utensils. South of the Holy Mother temple and north of uncle Kali’s house was the house of uncle Prasanna. The Mother spent a long part of her life in the cottage of uncle Prasanna, which has since been purchased by the authorities of the Ramakrishna Math and added to the Holy Mother temple properties, in which also are included the Punya-pukur and the new house of the Mother. North of this cottage was the gateway of the house of uncle Surya who was the son of Ishwarchandra Mukherji, one of the uncles of the Holy Mother. Her eldest uncle Trailokya was a Sanskrit scholar; but he died in youth soon after his marriage. The youngest uncle, Nilmadhav, remained a bachelor and never parted from Ramchandra.

After the death of Rampriya Devi, his first wife, uncle Prasanna married Suvasini Devi. He had two daughters— Nalini and Sushila (or Maku) by his first wife; and by his second wife he had two daughters, Kamala and Vimala, born during the Mother’s life, and a son, Ganapati, born after her demise. Uncle Kali had two sons, Bhudev and Radharaman, by his wife Subodhbala Devi. We have already said that uncle Abhay left behind him his widow

Surabala and an only daughter Radharani, affectionately called Radhu or Radhi. Uncle Prasanna had a moderate supplementary income from his priestly services in Calcutta. Owing perhaps to an early life of poverty, he was very frugal in his ways. With the money he saved, he purchased paddy fields and bullocks and thus improved his condition. Kalikumar was irritable by nature. It is said that before his birth his mother became very much overwhelmed by the loss of some children, when with the help of some medicines given by a woman who worshipped the goddess Kali and with her blessings too, she got Kalikumar as her son; and that accounted for the boy’s irascibility. Kali stayed at Jayrambati, and as an orthodox Brahmin he attended to his daily worship and the observance of ceremonies, so that he was greatly respected. Uncle Varada generally stayed at Jayrambati, though he often went to assist Prasanna at Calcutta.

The Mother spent her early days in a poor family; but poverty was in a sense a boon and made life sweeter by providing greater opportunity for her to reveal her affection for all around. Ramchandra could not raise enough paddy from his lands to meet the expenses of the family; so he grew some cotton also. Shyamasundari Devi would carry the little girl Sarada to the cotton field where she would lay her down and go to pluck the cotton pods. When Sarada grew up to be a little girl she would help her mother in this work as also in spinning sacred thread with the cotton, which would fetch some cash for cloth and other family requirements. Sarada had also to look after her brothers. ‘I used to go with them,’ she said, ‘to bathe in the Ganges, that is, in the Amodar, which was our Ganges1. After finishing our holy bath, I would eat with them some fried-rice there, and then bring them home. The Ganges had always an uncommon attraction for me.’ As for other engagements, she said, ‘As a girl I would plunge into neck-deep water to cut grass for the cattle, and walk to the fields with fried-rice for the labourers. During one year when locusts had nearly destroyed the crop, I went round the fields gathering paddy.’ As regards her education she said, ‘I sometimes accompanied Prasanna, Ramnath (a cousin), and others when they went to school in their boyhood; and thus I learnt a little. ’

In addition to these brief and casual references to her childhood days, some information can be gathered from her contemporaries. Thus Sri Raj Mukherji’s sister Aghormani Devi, a companion and playmate of the Mother’s girlhood days, said, ‘The Mother was very simple by nature; she was simplicity incarnate. Nobody had any altercation with her during childhood sports and games in which she very often played the master or the mistress of a house. She, of course, made dolls and played with them; but she preferred worshipping with flowers and bel leaves Kali and Lakshmi in images fashioned by herself. When other girls fell out, she would mediate, settle their quarrels, and reestablish cordial relations. Once during the worship of the goddess Jagad-dhatri, Sri Ramhriday Ghoshal of Halde-pukur was present. Finding the Mother lost in meditation before the deity, he kept his eyes fixed on her for a long time; but as he could not make out as to who was the deity and who the Mother, he left the place in fear.’ Other old people would say, ‘From her young days, Sarada was as diligent in her work as she was intelligent, quiet, and well-behaved. She had never to be asked to work. Of her own accord and with her own resourcefulness she would meticulously perform her duties.’

The self-identification of the Mother with Jagad-dhatri in her meditation which became pronounced enough to awe a casual observer was not an isolated event in this unique life. The girlhood days of the Holy Mother were made surprisingly singular by a strange combination of divinity and humanity, with a predominance of the former, as it were. Whatever others might think of her in her later life, she then generally revealed herself in her human role. But at the time of which we are writing, it seems as though she stood at the meeting point of heaven and earth and could not decide as to which side she should lean, fresh as she was from the world above; or it might have been that it was ordained from above that those early days should be divinely encompassed. So it is that the Holy Mother said with reference to those days, ‘Mind you, my dear, as a girl I saw that another girl of my age always accompanied me, helped me in my work, and frolicked with me; but she disappeared at the approach of other people. This continued till I was ten or eleven years old.’1 When she went into the water to cut grass for the cattle, there would appear a girl of the same age to assist her in the work. No sooner the Mother return from the shore after depositing a sheaf cut by the new girl, than she would find another sheaf kept ready in the meantime.

We have now an idea of how busy the Mother was in her early life. From her reminiscences of those days we also gather that she had off and on to undertake such hard tasks as cooking. But though she was a precocious and painstaking little girl, her hands were not strong enough for the whole arduous process, and so she had to call in her father for taking down heavy utensils from the fire-place. She had to fetch pitchers of water from the tank for domestic purposes, and she took this opportunity to learn swimming with the help of the pitcher.

When she was eleven years old (1864), the country-side was ravaged by a terrible famine. Her father had garnered some paddy; and though he was by no means affluent, he was moved so much by the appalling misery around that he opened his granary and started a free canteen. The Hoy Mother described it thus: ‘What a dire famine raged there once and how many starving people came to our house! We had stocked the previous year’s produce. My father had the paddy husked into rice and got potfuls of khichudi (hotch-potch) cooked by mixing it with black lentils. “Everybody in this house will eat this,” he said, “ and offer it to whoever may come. Only for my Sarada, a little rice of good variety will be cooked and she will eat it.” On some days the number of people became so great that khichudi ran short. Cooking would restart at once. No sooner was the hot food served on the leaves than I would fan it with both hands so that it might cool quickly. For, alas, the hungry stomachs could not brook delay! One day came a girl of either the (lowly) Bagdi or the Dome caste. The hair on her head had become shaggy for want of oil and her eyes were bloodshot like those of a lunatic. She ran to the tub where some rice-dust was soaked for the cattle and began gulping that. She wouldn’t heed the people who were crying out, “ Come in and eat the khichudiOnly after swallowing some rice-dust did she hear that call. Such, so dreadful, was the famine! After learning the bitter lesson of that year, people began to garner their paddy. ’

From the vivid picture drawn up by the simple, unvarnished, and incomparable words of the Mother we find how busy she was seeking to cool by fanning with her soft, delicate hands the hot food for the starving people, she who in future would reign in the hearts of hundreds with the irresistible claim of a mother! And how full of affection for that tender darling of a child was the poor Brahmin! The Mother’s life then was like that of any other girl in the village. But in the midst of this rural simplicity, now and then a sudden divine flash dazzles us. This interplay of light and shade could not perhaps entirely escape the notice of her brothers or of her parents who wanted to hug to themselves their small sister or smaller daughter as any other human being did. Perhaps because of the unforgettable impression of such moments of light, Shyamasundari Devi, mother of the Holy Mother, said in later life, ‘My child, I wonder who you really may be, my dear! How can I recognize you, my daughter!’ The daughter, of course, then brushed this compliment aside with apparent dislike, saying, ‘Who am I? Who can I be? Have I grown four hands (like any deity)? If so, why should I have come to you? ‘What Sarada Devi did as a sister becomes clear from a talk that she had one day with her mother. Shyamasundari Devi said, ‘Sarada, may I have a daughter like you in my next life!’ The daughter replied with a show of anger, ‘You will drag me down again! To think that I should come again to bring up your children! ’ With the memory of the quiet diligence of her affectionate daughter still fresh in her mind, Shyamasundari Devi repeated with an obvious appeal, ‘May I, indeed, get you again, my darling!’ Uncle Kali, too, once reiterated this compliment when he said, ‘Our sister is Lakshmi incarnate. She spared no pains to keep us alive. Husking paddy, spinning sacred thread, supplying the cattle with fodder, cooking,—in short, most of the household work was done single-handed by our sister.’

1. A lady devotee of the Master, and later a constant companion of the Mother.

1. Paush Samkranti, roughly corresponding to the winter solstice.

2. It is customary to have two names, one for astrological and the other for common use. We have it on the authority of Swami Gaurishwarananda, who had it from the Mother herself, that Kshemankari was the actual common name she was given. But her Mother’s sister, who had lost a daughter called Sarada, requested Shyamasundari Devi to change her child’s name to Sarada, so that the bereaved lady might imagine that the new child was one other than her own, though in another form.

1. The devotees of the Holy Mother consider her brothers and brothers wives as their own uncles and aunts. And so also her nieces are their cousins-whom they call ‘sisters’.

1. The popular belief, supported by scripture, is that all streams become as sacred as the Ganges at holy moments.

1. Much later, after the passing away of the Master, she had another vision of a similar girl (see the chapter on ‘With The Devotees’).

Leave a reply