Life

VALEDICTION

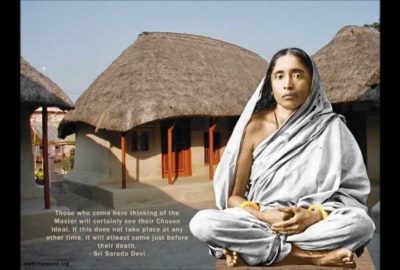

The Mother was at Jayrambati. The devotees decided to celebrate her birthday on December 13, 1919. To see the Mother on that auspicious occasion many devotees gathered there, while others sent offerings of clothes, flowers, fruits, and sweets. Owing to indisposition, she sponged her body with tepid water and wore the cloth sent by Swami Saradananda. When she had finished worshipping the Master, the devotees put vermilion and sandal-paste on her forehead and garlands round her neck. She sat there on her cot with her legs down, and the devotees came in one by one to worship her feet. It was not her custom to sit for her meal before her sons had finished theirs; but today she made an exception. At the request of all, she partook of the prasada after offerings had been made to the Master. Then the devotees and villagers were served with the prasada.

For some time the Mother had not been in good health. The strain of the birthday celebration brought about a relapse of the fever. At first all thought that it was her usual ailment which would soon yield to local treatment. But in spite of all that local physicians could do, the fever recurred intermittently and this made her extremely weak. It was noticed then that even a little temperature brought about complete prostration. Notwithstanding this, the Mother kept on initiating people during the intervals of the disease. As the devotees came from distant parts with great hopes, the Mother could not disappoint them even though such continuous strain drained away quickly her diminishing vitality.

Matters soon came to such a pass that no further reliance could be placed on local treatment and information had to be sent to Swami Saradananda, who, however, was then at Banaras in connection with some important work; and, as we have already mentioned, the Mother was loth to go the ‘Udbodhan’ in his absence. To add to the difficulty of the situation, the Swami had to hurry to Bhuvaneshwar just after his return from Banaras. When he next came to Calcutta, he realized that the Mother’s condition could brook no delay, and he, therefore, promptly sent Swami

Atmaprakashananda with two others to Jayrambati to take the Mother to Calcutta. The Mother readily consented to accompany them, and it was settled that at ten o’clock on Tuesday, February 24, the Mother would start for Calcutta with Radhu, Radhu’s mother, Maku, Nalini Devi, the widow of Navasan and Brahmachari Varada.

The Mother was then so weak that when she went to the chapel of Simhavahini two days before the day of starting, she became absolutely exhausted and said later, ‘It made me perspire like one on one’s death-bed.’ On the day of journey, she fell down on the landing steps of the tank (Punya-pukur) behind the house. The arrangement was that the Mother and Radhu would travel by two palanquins, while others would walk up to the Amodar and get into bullock-carts on the other side of the river. But Radhu refused to get into one of the palanquins, which the Mother allotted to Maku and her child without further ado. Early in the morning of the appointed day all left for Vishnupur except the Mother and Maku. The Mother got ready to start after finishing the Master’s worship. And then the villagers gathered round her and said with tearful eyes, ‘Come back soon after recovery. Don’t you forget us for long.’ ‘Everything is in the Master’s keeping;’ replied the Mother, ‘can I really forget you?’ And she wrapped the Master’s photograph in a piece of cloth, put it in a box, made a last salutation, and stood up to start. Crossing the outer gate, she saluted with folded hands in the names of Simhavahini and other village deities and walked slowly westward by the houses of her brothers. She would get into the palanquin after crossing the bounds of the village, as out of respect for the village deities she did not use any vehicle within its limits. Uncle Prasanna’s wife was standing there at their door with a pot of water and a basin to wash the Mother’s feet when she sat in the palanquin. The Mother said to her, ‘ You need not carry the water; hand over these things to Hari (Haripremananda); he will wash my feet. ’ The aunt obeyed and went in to get a glass of water, some sweets, and some pasted betel, with which she proceeded towards the Aher, the irrigation tank of the village. The Mother saluted the deity Yatra-siddhi-raya at Ghoshpara and turning back saluted the village of her nativity. Then she sat in the palanquin, when Hari washed her feet and the aunt handed over the sweets, the glass of water, and betel. The Mother took all these, and gave one of her cotton wrappers to Hari, as a memento, saying, ‘Hari, keep this.’

Varada moved along on a bicycle by the Mother’s side, and he intended to proceed thus to Vishnupur. They went westward while the villagers looked on with wet eyes. As the river could not be forded at the usual place because of the flood there at the time, their way lay through Shihar, which meant some two or three additional miles. At Shihar the palanquin was stopped by the Mother, who then washed her hands and feet and went to bow down to Shantinatha (Siva) at His temple, where she made an offering of some sweets, sugar, and molasses. As many boys and girls had gathered there, the Mother distributed some of the prasada among them as also to Maku and others, tasted a little herself, and the rest she kept aside in her hem for Radhu. When they reached Koalpara it was past eleven o’clock.

As soon as they reached there, Varada was told that the money for their expenses on the way had been left by mistake at Jayrambati in the house of uncle Kali, from where he was expected to fetch it without the Mother’s knowledge. After Varada’s departure the Mother found a mosquito-net missing, for searching out which she wanted him As he was nowhere to be seen, she asked him on his return as to where he had been. So he had to divulge everything. The net, however, was not to be found. Hence the Mother said, ‘All the signs appear to be inauspicious.’ According to the belief in those parts, the losing of anything on the way forebodes some evil.

It had been arranged that five of the bullock-carts would leave for Vishnupur that afternoon, the two palanquins with the Mother and Maku would start next morning, and the sixth cart would follow them in the afternoon Next day at sunrise the Mother went to the shrine-room at the Ashrama to salute the Master.

Afterwards, when the attendant met her at the Jagadamba-Ashrama, she said, ‘ So you are here! Why are you so late? It will be hot. Take this flower as a blessing for the start. ’ And she picked up a flower from the feet of the Master, touched it on to her head and then giving it to him said, ‘Tie it to a corner of your cloth.’ When the attendant bowed down before her, she made a little japa on his head and chest and kissed him touching his chin. At last she took leave of all and got into the palanquin. She had in her hand a stick with which she had been walking. This she now gave to Gagan (Swami Ritananda) for handing it over to uncle Prasanna, for it belonged to him She also gave him a mosquito-net for the uncle. And she said as she departed, ‘My son, there’s Sarat (Saradananda) to look after you all.’ As Gagan found no occasion for such a remark in the present context, he went on musing over it with some apprehension.

The palanquin moved on. After passing Kotulpur the Mother called Varada to her side to say, ‘Be always by my side, and keep your eyes open as you proceed. All the ornaments of Radhu and Maku are in the latter’s palanquin.’ This made Varada circumspect, and knowing as he did that the leader of the bearers was a devotee of the Mother, he called him to a solitary place to say, ‘Mother is apprehensive; you will have to be cautious on the way, particularly in the forest near Vishnupur.’ The leader said reassuringly, ‘We are thirty-two strong with a stout staff for each under the palanquins.’

At Jaypur the Mother ordered the palanquins to be lowered. The hut in which they had cooked last time when on their way to Jayrambati was now almost broken. The sight of it evoked a smile on the Mother’s face and she said, ‘Heyday! That’s our hut, my boy.’ She went near it, sat on a blanket under a tree, and brought out two rupees for fried-rice for a light repast for the bearers. Then she heated the milk for Maku’s son and went to the tank nearby to wash her hands and feet. Then she ordered a piece worth of fried-rice for herself and some more of the same stuff as also some fried things for Varada and Maku. When the fried-rice came, the Mother munched a little and then passing it on to others, she said, ‘I can no longer chew it.’ The journey was resumed after all had finished their meals.

The eight miles of the road from Jaypur to Vishnupur runs through such thick forest that one is afraid to pass through it even in the day-time. In the centre of the forest about four miles from Jaypur, there is a place called Tantipukur where a shop caters to the needs of the passers-by. When the party arrived at the shop they found some people of the labouring class chatting there. If they could get clear of the place somehow, they would come across scattered houses after another two miles, and hence there would be no cause for anxiety. But as soon as the Mother saw the shop, she said from her palanquin, ‘Ask them to lower the palanquin for a while; my feet are aching because of sitting long in the palanquin. Get from that shop half a pice worth of oil in a sal leaf. Let me rub it on the feet.’ Varada was alarmed to hear her speak thus, and he said in a whisper, ‘Some doubtful characters are sitting there; you should not get down; you sit there; I shall bring the oil for you.’ Then, again, Maku said, ‘I am feeling thirsty by eating the fried-rice; I shall drink a little water.’ The Mother said, ‘Why not drink? Go and do so from yonder pond.’ ‘To think that she should drink that water!’ remonstrated Varada quickly. But the Mother said, ‘ So many passers-by are drinking there. It won’t do any harm, go! You accompany her and help her to drink. ’ So they could leave Tantipukur only after purchasing the oil, and getting Maku’s thirst quenched.

The party reached Sureshwar Sen’s house at Gadadarja in Vishnupur at about two o’clock in the afternoon. Swami Atmaprakashananda and others had preceded them there by bullock-carts at about eight in the morning. They asked, ‘Why this delay?’ and began laughing at hearing that fried-rice eating was the cause; for the unusual liking for fried-rice of the people of Bankura is a matter of amusement for others. Sureshwar Sen had died a few months ago. The Mother said about him very feelingly, ‘Alas! Whenever I came here, my Suresh used to keep standing there with folded hands; he never even got up on the verandah. How great was his devotion!’ About him she used to say at times, ‘ Suresh was a second Girish Babu, as it were.’ The party stayed there the next day also, and started for Calcutta on the third day. They travelled in a third class bogie and reached the ‘Udbodhan’ at about 9 p.m on Friday, February 27.

Yogin-Ma and Golap-Ma were extremely concerned to find the Mother’s body reduced to a skeleton and accused her companions saying, ‘Dear me! How thin she looks! We could never realize that the Mother’s health was as bad as this.’ Swami Saradananda made all necessary arrangement for treatment from the very next day.

Dr. Kanjilal treated the Mother with homoeopathic medicine from February 28; and the fever subsided on the fourth day. But on the seventh day the temperature again went up to 101°, and the treatment showed no results. Kaviraj Shyamadas Vachaspati was called in on the fourteenth day. This new treatment bore fruit after about a week, from whence the Mother had no fever for a fortnight. This was extremely reassuring, so much so, that the devotees were one day allowed to come in and salute her. But after fifteen days there was a relapse, and along with that there arose a new difficulty. The Kaviraj prescribed an infusion of several drugs boiled together which was to be taken every morning. This was so bitter that the taste lingered till noon, so that the Mother could not relish any food, and therefore ate very little. The Kaviraj being informed of this said that he was helpless since his system of medicines knew of no drug that was not bitter for this disease. As a last resort Dr. Bepin Behari Ghosh, an allopath, was entrusted with the treatment from April 8. He treated her for about a month; but as no definite result was visible, Dr.

Pranadhan Bose, a noted physician, was called in on May 1, and the help of Dr. Sureshchandra Bhattacharya and Dr. Nilratan Sarkar was also taken for a proper diagnosis of the disease. At last on May 16, Dr. Bose declared that it was a case of kala-azar. The doctor tried his best to bring the disease under control, but by June 1, it became apparent that the allopathic physicians had given up all hope of recovery. As a last resort, therefore, the indigenous system of treatment was resumed on that date by Kaviraj Rajendranath Sen who was helped by Kaviraj Kalibhushan Sen. Kaviraj Shyamadas Vachaspati, too, came again. His pupil, Kaviraj Ramachandra Mallik, visited the Mother every day and prepared the medicine with his own hands. During the last three days Dr. Kanjilal administered homoeopathic medicines once again.

In fact, from the day that the Mother came to the ‘Udbodhan’, Swami Saradananda did all that lay in his power to get the Mother restored to normal health. Apart from medical treatment, he tried to enlist in the cause the supernatural agencies also. But there was no sign of improvement in her condition. Her temperature rose three or four times each day, and when it went very high up, she lost consciousness. It was summer, and the excess of bile produced such a burning sensation all over the skin that the Mother used to say, ‘I shall dip my body in the water of a pond covered with weeds.’ The attendants cooled their hands over ice and passed them over her body. If there was no ice, the Mother placed her hands on the bare bodies of those who had low temperature. The continuous suffering turned her into a veritable little girl. As she felt no comfort on her bed, she called in her attendant Rashbihari one morning and said, ‘ Seat me on your lap. ’ Sarala Devi, another attendant was near at hand, and so Rashbihari said to her, ‘ Seat the Mother a little on your lap, you are a woman. ’ As she kept silent, a few pillows were arranged in a pile and the Mother was seated reclining on them; and she was otherwise consoled.

Even in the midst of this ordeal, her tender motherly heart was ever solicitous for the welfare of all. Indeed, it had an even more charming expression at that time. When the attendant came to the Mother in the morning, before going to the Kaviraj’s house, to inquire about her condition, she would invariably say, ‘Eat before you go; for you will be late in returning.’ When the Kavirajas went down after seeing her, she used to say, ‘Give to the grandson (Kalibhushan Sen) of the old man (Durgaprasad Sen) some refreshment — some sweets, some mangoes. Give to Ram Kaviraj, and the old Kaviraj (Rajendranath Sen).’ The Mother showed the same affection to Drs. Jnanendranath Kanjilal, Durgapada Ghosh, and Shyamapada Mukherji whenever they came; and she made tender inquiries about them and their families. One day, when Prabhakar Mukherji and Manindra Bose of Arambagh came, she asked them in a faint voice, ‘Are you well, my dears? Shall I live? I can’t eat anything and am very feeble.’ Then she inquired about that part of the country, ‘Has it rained?’ Manindra Bose had sent some green palm fruits with a woman named Ramani who was known to the Mother. The Mother remembered the fact and said, ‘I didn’t know when Ramani came; I was unconscious owing to the fever. Tell her not to be sorry on that account.’ Swami Adbhutananda (Latu) was then seriously ill at Banaras. The Mother was aware of this, and hence she used to ask any one coming from there, ‘How is Latu?’

Many were present at the ‘Udbodhan’ who would feel blessed if they could serve the Mother in any way; but the Mother avoided such service so scrupulously that it was hard to get an opportunity. One day, as she lay down to have a little rest after taking her noonday diet, an attendant thought that to be an excellent opportunity for fanning her so that she might have a good nap. But he had moved the fan for some four or five minutes only, when the Mother said, ‘It’s no more necessary; your hand must be aching.’ The attendant explained that a hand-fan does not tire one out so easily and that he would stop as soon as it became tiresome. But after a few minutes the Mother reopened her eyes to repeat, ‘No, my son, your hand will ache; you stop; I shall sleep without it.’ As the attendant did not stop even then, she said soon after, ‘My dear boy, I can’t have any sleep thinking that your hands will ache. You stop the fan, then I can sleep without any anxiety.’ The fan had to be stopped at last; the attendant could serve hardly for ten minutes.

On his first visits Dr.Pranadhan Bose was paid sixteen rupees daily as his fees over and above his taxi fare. One day somebody sent for the Mother plenty of fruits, flowers, sweets, and curd. In the evening, when the doctor was talking downstairs with Swami Saradananda after examining the patient, some of these things were placed in his car according to the Mother’s direction. Seeing these presents the doctor looked happy. Next day, when he came for his daily visit, he looked round the room a little more closely to find a picture of the Master there. He was a Christian, but had a very liberal mind, which was moved by all he saw. Going down he asked Swami Saradananda as to who it was that he had been treating all those days. The Swami explained everything and in the course of the conversation told him that the expenses were being defrayed by the devotees. From that day the generous doctor stopped charging fees; nay, when the treatment was changed a few days later, he kept coming every day, paying the taxi fare himself and spending a good deal of time at the ‘Udbodhan’ inquiring about his patient.

Equally with her kindness and politeness for all was noticeable her loving behaviour towards all her relatives during the early stages of her illness. In the middle of March, her nephew Ramlal came to see the Mother with his sister Lakshmi Devi and others while on their way to a celebration at Entally in Calcutta. After some time had elapsed in conversation, the Mother told Lakshmi Devi of Yogin-Ma’s illness. Lakshmi Devi then went to see her and from there proceeded to Entally without revisiting the Mother, who had, however, been expecting her. Finding at last that they had departed, she told Brahmachari Varada, ‘Look here! In the course of the conversation I forgot to give a cloth and some money to Lakshmi. You now go to Entally with Kestolal (Swami Dhirananda) to witness the celebration and give the cloth and money to her. They decorate the Master tastefully at Entally.’ With this she ordered somebody to take out two rupees and a piece of cloth with a fine border to be handed over to Varada for presentation to Lakshmi Devi.

In the midst of this suffering, again, she helped her disciples in the path of spirituality and initiated at least one fortunate man. In these matters she paid no heed to warnings that she should not strain herself.

On her sick-bed she had to sustain three shocks. Swami Adbhutananda passed away on April 24, and Ramakrishna Bose, a disciple of the Mother and son of the noted devotee Balaram Bose, departed on May 14. It was decided that in consideration of the Mother’s condition, the news should be withheld from her. But Golap-Ma inadvertently divulged it all, with the result that the Mother wept sending up her temperature. She had little sleep that night. A week after the death of Ramakrishna Bose, uncle Varadaprasad succumbed to pneumonia at Jayrambati.

This was also kept back from her. She knew that he was seriously ill, and therefore inquired now and then, ‘How is Varada?’ But after her brother’s passing away, she put a different question. ‘Is Varada no more? I saw him standing near the railing (on the verandah) and looking at me.’ Then the truth had to be told. This was very poignant to the Mother; she could not control her tears at the loss of this beloved brother.

But we must not merely give attention to her tears and sorrow; we must also take note of her nonattachment. She wept for her brother; but from Brahmachari Gopesh we have an account of what happened only a few days later. Writes he: ‘At that time I was very much surprised to hear what the Mother said one day. A few days earlier, uncle Varada had died. Although the Mother was momentarily overwhelmed with grief at that, she soon wiped it away from her mind. She passed on the news to me thus with absolute unconcern, “Did you hear? Varada is dead.” At first I failed to understand whom she was talking about, for it was altogether beyond my imagination that she could tell of the death of her very dear brother without any emotion. So I kept on looking at her quizzically. Then the Mother explained, “Father of Fudi (Kshudi) of Jayrambati.” The news made me extremely sad; but my surprise at the absence of any pang on the Mother’s part was even greater. ’

Some still more astonishing events followed to convince the devotees very rudely that the Mother was gradually gliding out of this world of attachment, and that the sweet snares, which she had voluntarily woven round herself, were being rent asunder one by one. When in the middle of March a devotee said, ‘Mother, your health has deteriorated badly this time. I never saw your body so weak’, the Mother replied, ‘Yes, my son, it has become very weak. Methinks, whatever work of the Master was to be done by this body is over. Now the mind hankers for him only, and likes nothing else. See, for instance, how I loved

Radhu, and how much I have done for her happiness and comfort; but now my mood is changed. When she comes to my side now, I feel unhappy and I begin thinking, “Why does she come here to try to drag down my mind?” The Master kept my mind bound down by all these things for the sake of his work, otherwise could it have been possible for me to stay on after he left?’

The mind was really getting detached. When tossing about in her bed owing to the intense fever, she was often heard to say, ‘Take me to the side of the Ganges; I shall feel cooler near the Ganges.’ It seemed as if she wanted to be freed from all old associations. Swami Saradananda searched for a house on the bank of the Ganges, and there was talk of taking her to Banaras. But the physicians said that removal at that stage was inadvisable.

So there could be no change of place. But that could not certainly prevent her from getting rid of entanglements. Gauri-Ma and Durga Devi used to visit the Mother every day while returning from their bath in the Ganges. They then sat by her for some time and fanned her. But one day as they came there, the Mother said, ‘Don’t touch me. Why do you come every day to annoy me—for what purpose, and to see what?’ This unexpected indifference came like a bolt from the blue, and Gauri-Ma said imploringly, ‘Mother, you are lying ill, and we find no peace of mind. We want to be always by your side, but can’t find time. That’s why we come once in a day to you. ’ The Mother still persisted in the same strain, ‘What will you gain by coming to me? I can no longer bear to hear anybody’s problems.’ Then she cooled down and added, ‘Even if you come, don’t enter my room, See me from outside that door and depart; and don’t make me talk on any matter.’ Gauri-Ma was thunder-struck! She could speak no more, but shed profuse tears and took leave with a heavy heart. From the next day they came at the usual time, but without entering the room, sat for an hour at the place indicated by the Mother, and through silent tears communicated the grief in their hearts. The Mother saw all this, but remained remorseless.

Next came Radhu’s turn. Yes, Radhu too, was rejected, though this may sound unbelievable. A few days before the Mother passed into Life Eternal, she said to Radhu, ‘Look here! You go away to Jayrambati; don’t stay here any longer.’ And to her attendant Sarala Devi, she said, ‘Ask Sarat to send them to Jayrambati.’ Sarala Devi inquired, ‘Why do you want them to be sent? Can you live without Radhu?’ ‘I can do so well enough,’ replied the Mother firmly. ‘I have dissociated my mind (from her).’ When Sarala Devi communicated this to Yogin-Ma and Swami Saradananda,

Yogin-Ma asked the Mother, ‘Mother, why do you want them to be sent away?’ The Mother answered, ‘In future they will have to stay there as a matter of course. Hari is going; send them along with him I have withdrawn the mind, and there’s no more need for them’ Yogin-Ma implored, ‘Don’t you be saying so, Mother. If you withdraw your mind, how shall we live?’ But the Mother whose vision was now directed towards the Infinity beyond all delusion, said with disconcerting indifference, ‘Yogin, I have discarded all attachment, no more of that.’ What more could Yogin-Ma add where pleading was of no avail? Morosely she went to Swami Saradananda and related the whole affair. He drew a deep, heavy sigh and said helplessly, ‘Then we can no longer hold back the Mother. Now that she has taken off her mind from Radhu, there’s no further hope.’ He then said to Sarala Devi who was near at hand, ‘All of you try if the Mother’s mind can be brought back a little to Radhu. ’ But their efforts bore no fruit. On the contrary, understanding their motive the Mother said without any ambiguity, ‘Know it for certian that the mind that I have turned back will not come down again. ’

As days rolled on, this resolution of the Mother became all the more pronounced and filled everyone with desperation. Soon after Brahmachari Hari left for Jayrambati, the Mother asked Varada, ‘Why did not Radhu, Nalini, and others go away to Jayrambati with Hari? You escort them all there.’ Swami Saradananda being informed of this development was quite at a loss to fix upon any course of action. Other devotees, too, thought, ‘Radhu is dear to the Mother as the apple of her eye; she is so fond of Radhu that it is hard for her to live one moment without her. Even while on sick-bed she often inquired about Radhu and her son. And now she is eager to send them away to Jayrambati, even though her own condition is so very bad. It all passes one’s imagination.’ But if people could not understand the Mother’s disposition at that time, or they refused to believe what they witnessed, in a short while her determined attitude dispelled all doubts from their hearts. Noticing the Mother’s irritation, Nalini Devi dared not approach her any longer, and she shed silent tears. At last she said in dismay, ‘If our presence is galling to aunt, we may as well go away. But what will people say? They will think, “Look at this! The Mother is so seriously ill, and these have come away deserting her at this time!”’ Swami Saradananda therefore, pleaded with the Mother, ‘It will pain them to go away during this illness of yours. They will leave as soon as you recover a little.’ The Mother still persisted, ‘Well, it will be better if they are sent away. In any case, see that they don’t come to me any more. I have no desire to see so much as their shadows any longer.’ So completely free had she become! For ten days before the final departure, the Mother slept on a bed spread on the floor. One day at noon when Radhu was asleep and an attendant was sitting by the Mother, nursing her, Radhu’s baby Banu got up from sleep and crawling to the Mother’s side tried to climb on to her breast, as was his wont, when the Mother said to him, ‘I have totally freed myself from all fondness for you. Go, go, you can no longer succeed.’ Then to the attendant she said, ‘Lift him up and keep him on that side. I don’t like these any longer.’ The attendant took the baby into his arms and left it with its grandmother in the adjoining room.

The Mother’s condition was worsening. Her frame became so shrivelled that it seemed to be indistinguishable from the bed. The physicians gave up all hope and the Mother, too, realized this. When she suffered similarly on the previous occasion she had said, ‘I shall have to suffer likewise over again.’ This time, when her affectionate attendant supplicated, ‘Mother, you can certainly stay on if you just wish to do so’, she simply said, ‘Who indeed wants to die?’ She had no will of her own then, she had resigned herself entirely to the Divine wishes; and keeping her ears pricked up for the last call she said, ‘I shall go, whenever he takes me.’ She incarnated for the good of all; and in order to establish contact between her free mind and this world of small interests, she adopted Radhu as a medium with whom she had a tie of affection. Now that tie was cut asunder; and when Radhu came to the Mother’s room one day, she said to her, ‘I have let loose (my mind) from its post. What will you do to me? Am I a human being?’ These were the last words she spoke to Radhu. As Radhu knew the Mother only as a mortal, she did not so much as try to comprehend the meaning of those words uttered so unexpectedly; and the Mother, too, gave her no opportunity to do so.

About a month before the last day, she asked the picture of the Master that she worshipped at the shrine to be removed to some other room, for she explained that it would be presently impossible for her to go out even when necessary, and that a sick-bed and shrine could hardly be in the same place. Her direction was obeyed.

Seven days before the passing away, she sent for Swami Saradananda at about 8-30 a.m He came and knelt near the Mother’s feet on the left side and tried to caress her hand with his. She promptly held his right hand under her left and said, ‘ Sarat, I leave them all with you’, and as quickly drew away her hand. Swami Saradananda suppressed his tears with difficulty and with a heavy heart moved out of the room, walking slowly backward and keeping his eyes fixed on her.

There were then two classes of attendants—the monks and

Brahmacharis, and the women devotees. The monks went to the doctors, brought medicines, procured milk, prepared liquid diets, and fanned the Mother. The women cooked rice, administered the diets, washed clothes, cleaned the bed, and did other things in general. The Mother then behaved like a little girl— she was simple, importunate about trifles, and yet totally without any interest in anything. One midnight as Sarala Devi wanted to feed her, the Mother said petulantly, ‘I won’t eat. You have only two sentences, “Mother, eat”, and “Mother, apply the stick (thermometer)”.’ Sarala had learnt a trick to make her change her mood under such circumstances. She had only to suggest that it would be best to call in Swami Saradananda to rectify any defect that there might have been; and the Mother would at once become reasonable and behave like a good girl. So she tried the remedy tonight and said,’ Mother, should I then call in Maharaj (Swami Saradananda)?’ The Mother still remained intractable and said, ‘Call Sarat. I won’t eat from your hand.’ Swami Saradananda came immediately. Making him sit by her, the Mother said, ‘Do pass your hand over my body a little, my son.’ And taking hold of both his hands she added, ‘See my son, how much they vex me; they can only say, “Eat, eat”, and they can only apply that stick (thermometer) under the arm. Tell her not to pester me any more.’ Swami Saradananda said softly, ‘No, Mother, they won’t vex you any longer. ’ Having consoled her in this way, he said after a little while. ‘Mother, will you eat a little now?’ The Mother said, ‘Give.’ When the Swami asked Sarala Devi to bring the diet the Mother said, ‘No, you feed me; I won’t take from her hand. ’ The Swami took the feeding cup in hand and held the nozzle to the Mother’s lips. When she had drunk a little milk from the cup, the Swami said, ‘Mother, rest a while and then drink again.’ Greatly pleased at this consideration, the Mother said, ‘Just see, how finely he speaks, Mother rest a while and then drink again!” Don’t they know how to speak such a simple thing? Just see how she has worried my son at this dead of night! Go, my son, and sleep. ’ And with these words she patted his back a little. The Swami arranged the mosquito-net and said, ‘Good night, Mother.’ The Mother said, ‘Good night, my son. Alas, how my son has been disturbed!’ Up till then the Swami had been cherishing a desire to render some personal service to the Holy Mother, whose shyness, however, stood in the way. But before she finally took leave of him, she gave him an opportunity to have his desire fulfilled.

That an infinite affection influenced all that the Mother did up to her last moment is proved by her extreme consideration for Swami Saradananda as revealed in the last incident. Her love for Sarala Devi was equally tender as the subsequent event proves. Sarala Devi could well understand the vexation of such a patient at being asked to take diet and to use the thermometer so frequently; and hence she suggested to Swami Saradananda to change the duties. He complied and accordingly Varada and the widow of Navasan did Sarala’s duties for two days during which time Sarala Devi kept herself studiously aloof. The Mother did not fail to notice this and made constant inquiries about her. At last at noon of the second day the Mother had Sarala called to herself, and placing the latter’s head on her bosom, she said, ‘Are you angry with me, my daughter? Don’t you mind, my dear, if I have said anything. ’ Sarala could say nothing, but began shedding tears, and she resumed her duties.

As a result of the disease, the Mother’s hands and feet became swollen and she could not move out of the bed. Sudhira Devi of the Nivedita School with her girl students stayed by the Mother’s side by turns to fan her and help the attendants in other ways. There were now only five days left, when a woman devotee known as Annapurna’s mother came to see the Mother. But as admission was prohibited to outsiders, she stood at the door-way. Just then the Mother turned over to a side and noticing her there, beckoned her to enter. The devotee came in and said with a choked voice, ‘Mother, what will be our lot?’ In a very tender but feeble voice the Mother said, ‘What fear is there? You have seen the Master. What fear can there be for you?’ She stopped for a while and then added slowly and softly, ‘But one thing I tell you—if you want peace, my daughter, don’t find fault with others, but find fault rather with yourself. Learn to make the world your own. Nobody is a stranger, my dear; the world is yours.’ These were the last words of the Mother of the Universe to those afflicted souls for lightening whose burden She incarnated Herself out of Her infinite compassion undergoing all these ordeals of life on earth.

For three days preceding the departure, she hardly spoke, but remained merged in her Self; she felt disgusted at any attempt to drag down the mind to the physical plane. Gradually she stopped talking altogether. To a weeping attendant her last consolation was, ‘There’s Sarat (Saradananda); don’t be afraid.’ At last at 1.30 a.m. on July 21, 1920, she drew a few heavy breaths and then entered into Mahasamadhi. The long disease had made her frame skeletal, the eyes sunken, and complexion dark. But in the peace and silence of the final departure her face became free from all signs of affliction and regaining its usual fullness shone with ethereal luster which lasted even when the body became cold, so much so, that owing to that placid brilliance, many on-lookers could not believe that life had become extinct.

Next morning (July 21), under the leadership of Swami Saradananda, the devotees decorated the body with flowers and garlands and carried it on their shoulders singing in chorus the Rama-nama kirtana. The procession started at about half past ten and proceeded from the ‘Udbodhan’ northward to Baranagore, just opposite the Belur Math. There they crossed the Ganges in boats and laid the body on the bank of the river at the Math. A large number of devotees had gathered there by that time. The women now took charge of the body and bathed it in the sacred water of the Ganges. The pyre of sandal wood was lighted at about three o’clock in the afternoon, on the bank of the Ganges, a few yards north of Swami Vivekananda’s temple. The body was offered there as a sacrifice. In the meantime the other bank of the river was overcast with clouds. Then followed a shower. The devotees apprehended that this might interfere with the funeral fire. But nothing happened on the western bank till nightfall. When at dusk all was finished and Swami Saradananda poured out the first pitcher of Ganges water for putting out the fire, a heavy shower came down to extinguish it completely without any further human endeavour. The Mother’s corporeal body was there no more, the fire was out, and the devotees slowly returned home with a natural shower of benediction pouring on their heads.

* * *

On that sacred spot was erected a small temple and on the Holy Mother’s birthday on December 21, 1921, it was duly consecrated. The Holy Mother is still there receiving daily adoration from her sons and daughters and attracting many others from countries all over the world and filling their hearts with bliss and plenitude.

Peace! Peace!! Peace !

If you want peace, don’t find fault with others, but find fault rather with yourself. Learn to make the world your own. Nobody is a stranger, my dear; the world is yours.

Leave a reply