Life

THE MOTHER AND THE MASTER

We have discussed how the Master looked upon the Mother. Now we shall try to understand how the Mother estimated the Master. For this we have no great need to turn back to the Dakshineswar and Cossipore days though for bringing out the essential idealogical factors we may have to retrace our steps a little. For the rest we shall keep our vision directed in front.

One day, as the Master sat on his smaller cot in his room at Dakshineswar, and there was none except the Mother who was sweeping the floor, she suddenly asked him, ‘Who am I to you?’ Without the least hesitation the Master replied, ‘You are my Blissful Mother.’ Again, when Hridaya one day asked the Mother banteringly, ‘Aunt, don’t you call my uncle your father’, the impromptu answer came from her lips, ‘Why do you speak of him as father only? He is mother, father, friend, relative, acquaintance, my nearest and dearest, and everything.’ As the Master considered the Mother to be the Divine Mother, the Master was to her the embodiment of all the gods and goddesses; and this she once openly declared by saying, ‘He is the goddess Manasa and Ganga, and all.’

It was the second week of June 1913. Dr. Durgapada Ghosh and Sri Surendranath Bhaumik were having a little talk with the Mother before leaving her village home. Surendranath submitted that he had a little difficulty in worshipping the Master, for though he had a vague idea about the identity of the Master with his own chosen Goddess, and so he could worship his chosen Goddess in the picture of the Master, yet he was faced with an incongruity every time he tried to utter the mantra, ‘With your grace, O Great Goddess, etc.,’ at the time of dedicating the fruits of his japa to the deity on the completion of the worship. The Mother replied with a hearty laugh, ‘Well, my boy, he himself is both the Great God and the Great Goddess. He is in all the deities and he dwells in all the creatures. One can worship all the gods and goddesses in and through him. You may as well call him the Great God as the Great Goddess.’ Another day (end of March 1920), she said to a lady devotee, ‘He is everything. He is the Purusha (the Supreme consciousness) and he is the Prakriti (the Primordial Energy). From him everything will flow.’ At Jayrambati the Mother at the time of initiating a devotee, asked him to offer at the

Master’s feet all his works, virtues and vices, merits and demerits; and then pointing to the Master as his guru she gave him the mantra. But the devotee thought, ‘If the Master is the guru, what is the Mother then?’ For he could not realize that the two were but one. And hence he asked her, ‘How am I to think on the Master?’ The Mother solemnly reiterated, ‘He is all—Purusha and Prakriti. If you think on him, you have thought of all.’ To a lady devotee the Mother said, ‘In the Master are all the deities—not even (the goddesses) Sitala and Manasa excluded. ’

At one time they used to bring for her from the temple of Siddheshwari at Baghbazar the water with which the deity had been bathed. One day, after the worship of the Master, Swami Vasudevananda brought to the Mother in two separate pots, the bath waters of the Master and Siddheshwari. ‘Why two?’ inquired the Mother. When the matter was explained she said, ‘It’s all one.’ As Vasudevananda still held before her the two pots, she said, ‘Mix them up.’ ‘I shall do so from tomorrow,’ said the Swami. But the Mother insisted on these being poured into the same pot then and there, and she drank that mixed water.

We read in several Bengali works1 that though the Mother was so very shy that she never went to the Master’s room when any gentleman or even a devotee was there, yet when the Master passed away at Cossipore, she could contain herself no longer, but rushed to the room and cried out, ‘Mother Kali, dear, for what fault of mine have you left me’

From such statements and incidents, it appears clear to us that the Mother did not look upon the Master as a mere husband or man, nor even as an ordinary immortal; according to her, he was none other than the all-pervading God Himself. Hence her instruction to the devotees was, ‘The Master is everything —he’s the guru, he’s the chosen Deity.’ And about one of her experiences she told Sudhira Devi, ‘I was in such a state at one time that I could not even drive away an ant from the food offered (in front of the Master), under the belief that the Master himself was eating it. ’

She identified the Master with all the deities and all creation, including even an ant. And her conception of him transcended all forms and ascended to the formless Brahman. Though the Advaita Ashrama at Mayavati on the Himalayas is dedicated to non-dualism, the great Swami Vivekananda, during his visit there in early January 1901, found that a shrine-room containing the picture of Sri Ramakrishna had been established and that regular worship was being conducted with flowers, incense, and other paraphernalia. The Swami vehemently denounced this dualistic tendency but he did not order the discontinuance of the worship, as that would hurt the feelings of others. He rather believed that they would realize their mistake and rectify accordingly. The Swami’s criticism had the desired effect, and the shrine was broken up. One who still doubted if it was right for him to profess himself a member of the Advaita Ashrama when he leaned towards dualism appealed to the Holy Mother as a final resort, only to receive the reply, ‘Sri Ramakrishna was all Advaita and preached Advaita. Why should you not also follow Advaita? All his disciples are Advaitins.’

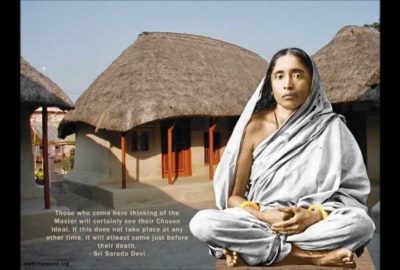

Just as the Master, though himself a doyen of Advaitins and ever established in non-dualism, found nothing incongruous in having apparently diverse attitudes towards Reality—non-dualistic, qualified non-dualistic, or dualistic—according to the level on which his mind worked for the time being, so also the Mother could offer worship to the Master at the same time that she knew him as the supreme Brahman. From her own account it appears that the first real worship of the Master originated with heiself, just as the worship of Sri Chaitanya began with his wife Vishnupriya who had the first image of her consort carved out of margosa wood and had it installed in a shrine. The Mother said that the first copy of the photograph of the Master that is now worshipped in thousands of homes, became so black that it had to be rejected and given to a brahmin of Dakshineswar at his request. When some time later the brahmin went away from the village, he left the photograph with the Mother, who placed it along with other deities and went on offering flowers and food. One day the Master entered the Nahabat and noticing the picture there, said, ‘Hullo, dear, what’s all this you are doing here?’ The Mother, who was cooking under the staircase, came in, attracted by the Master’s voice, to find him offering once or twice to that picture some of the bel leaves and other things that were there for worship. The owner of the picture never returned; and so it became the Mother’s constant companion. It was dark at first, as we have said but gradually it became lighter. The Master got her daily worship. Even during long journeys, she had the picture with her, and made it a point to offer something to it. There was no sanctimoniousness about this worship, though there was enough of love and earnestness. At the time of worship it seemed as though she was sitting in his living presence and acting accordingly, with the greatest intimacy. We quote from one who witnessed this worship day in and day out:

‘The framed photograph of the Master rested on a wooden seat in a niche in the wall; and by its side were the image of the child Gopala, and one or two more pictures of other deities. In the morning after taking a little of Ganges water in hand the Mother roused the Master from his sleep—kept erect the picture that lay in sleep. Under the Master’s seat in a small brass Kamandalu was Ganges water, and near it were sandal-wood, a stone piece on which to make sandal-paste, apanchapatra, and some more paraphernalia for worship. After finishing the domestic duties, the Mother sat at about nine’o’clock in the middle of the room, placing the Master in front. She bathed and worshipped him there with offerings of flowers, sandal-paste, fruits, sweets, syrup of sugar-candy, and halva (a sweet preparation made with sugar, butter, and semolina). Then she sat erect in meditation for some time with her hands on her lap. She devoted more time to this worship whenever she had no other special engagement; but she never took too long. She seemed to lose her ordinary consciousness during meditation, after which she made her obeisance to the Master and kept his picture in its previous position. At the end, she took a little of the water with which the Master’s feet had been washed, and little bits of tulasi and bel leaves, if there happened to be any. As flower was a rarity at Jayrambati she used them as often as she could get them. In the absence of flowers, tulasi leaves and water served her purpose. For tulasi she had a certain predilection which she expressed thus, “”Tulasi is very pure; everything is sanctified if tulasi is there.” At noon rice, soup of lentils, and vegetable curries were offered in the Master’s name in the kitchen. In the evening, again, she offered to him luchi, chapati, vegetable curry, milk, molasses, etc. There was no regularity as regards offerings in the afternoon. If any special thing came there by chance, it was offered at about four. ’

This was all the formality. And then, as to intimacy, we learn that when she was leaving Koalpara for Calcutta for the last time, Brahmachari Varada went to her room at five in the morning to find that she had finished worshipping the Master with fruits and sweets and was then saying to him while wrapping the picture with a cloth, ‘Get up, it’s time to start. ’ At another time, when the Mother was at Jayrambati, during. Jagad-dhatri worship, a devotee found the Mother finishing the Master’s worship early in the morning and then at the time of offering food to him saying, ‘Mind you, Mother (Jagad-dhatri) is to be worshipped today. Do finish your meal early, for I shall have to go there.’ On a third occasion, when there was talk of the Mother’s going to her village from Calcutta, but because of the sickness of one or other of her retinue the date was being repeatedly deferred, she was heard saying to the Master, ‘Let us go to Jayrambati. Don’t you have any liking for the big tank and the tulasi leaves there?’ After the dedication of food to the Master, she actually saw him tasting it. When Dr. Lalbehari Sen was on a visit to Jayrambati in 1911, he fell ill. When convalescent, he was given a little khichudi as diet by the Mother. As the doctor hesitated, fearing that the food would do him harm, the Mother assured him that he need have no apprehension since the Master had partaken of it. At this the doctor querried, ‘Can the Master be seen?’ The Mother replied, ‘Yes, nowadays he comes at times and wants to eat khichudi and cheese.’ As somebody regretted at Koalpara that though food was offered to the Master, one could not know whether he accepted it or not, the Mother averred emphatically, ‘There’s no doubt that he does eat, my boy; if the dedication is made from the bottom of one’s heart, he surely eats it. ’ And she added that when she calls the child Krishna for his meal, he goes to her jingling his anklets and eats with a childish clamour. In November 1914, a woman devotee on entering the chapel heard the Mother addressing the Master thus like a bashful newly married maiden, ‘Come, come for food,’ and then approaching the image of the child Krishna she called him, ‘Come Gopala, come for food.’ As the Mother’s eyes fell suddenly on the woman devotee, she smiled and explained, ‘I am taking them all with me for their meal.’

And as the Mother proceeded towards the kitchen, the devotee felt as though the deities were actually following her.

In truth, the Mother visualized the Master’s physical presence in the picture, which consciousness of living communion persisted even in her sleep. One day, the worship was done by somebody else. As the Mother rested in her bed after lunch, she dreamt that the Master lay on the floor. In wonder she asked, ‘Why do you lie down here?’ and as she spoke, she woke up to find to her horror that the worshipper had left the flowers touching the Master’s picture, so that the ants had crept on to his body from them. She got down from her cot immediately, removed the ants and the flowers, and warned the worshipper for the future.

When staying at the Nivedita School premises owing to Radhu’s malady, the Mother was asked one day by Sarala Devi regarding the method of consecrating food. The Mother replied, ‘Look here, my dear, consider the

Master as your very own and say, “Come, sit, take, eat.” And you should think that he has come, is seated, and is eating. What need is there of mantras and such formalities with regard to one’s own? Those things are like the courtesies and considerations one has to show when one’s friends and acquaintances come on a visit; for one’s own, no such thing is necessary. He will accept your gift whatsoever way you may offer it. ’ Of course, she taught some mantras and also a little ceremonial, when a devotee showed much eagerness for these. For instance, she taught Sarala Devi the mantra for dedication of food after drawing the latter’s attention to the fundamental attitude of love. To another devotee she said (June 1914), ‘One should be careful not to be guilty of neglecting the rules of service. There should be no hard particle in the sandal-paste, and the flowers and bel leaves should not be worm-eaten. One should not touch one’s limbs, hair, or cloth with the hands when one is engaged in the worship or in the duties connected with it. These should be done with extreme care. And food and other offerings have to be made in proper time.’ But she did not forget to modify such statements thus: ‘But one thing you should know. He always forgives men knowing them to be ignorant.’

She impressed indelibly on her disciples’ hearts that the Master is all. To Swami Kapileshwarananda, she said, ‘Mark you, I haven’t given you the mantra; it’s the Master who has done so.’ Such statements naturally aroused curiosity in the minds of the devotees. ‘What exactly is the relationship between the Master and the Mother? ’ In exceptional circumstances the Mother herself intimated their identity. To Sri Manadashankar Dasgupta, she wrote in a letter dated the 5th of Chaitra (March) 1917, that if he felt more inclined towards meditating on her, he could do so, because there was no difference between the two personalities except that of form, and that in fact the same entity that indwelt the Master’s body inhabited the Mother’s also. The letter that she sent three weeks later also affirmed, ‘He who is the Master, am I.’ To make the point clearer, Sri Dasgupta asked the Mother on meeting her, ‘Mother, should I do japa of the Master’s name during meditation?’ The Mother replied, ‘Yes, you should.’ ‘Why, where is the need?’ he asked again. ‘You and the Master are but one.’ ‘No, no,’ hastily corrected the Mother. ‘Though one, I can never advise the omission of the Master’s name.’ One day the Mother was talking with a monastic disciple who asked, ‘Does the Master appear to you always, does he eat from your hand even now?’ The Mother posed a counter question, ‘Are we distinct?’ and simultaneously she bit her tongue with her teeth, as if retracting, saying at the same time, ‘What’s this that I have uttered!’

In the course of a conversation, no sooner did Swami Keshavananda express his sorrow at not having been able to see the Master when he incarnated than the Mother pointed to her own person and said, ‘He is here in the body in a subtle form. The Master himself declared, “I shall live within you in a subtle form.”

At the time that Sri Nareshchandra Chakravarty went to Jayrambati with two candidates for initiation, the Mother, wishing to accept his worship, directed him to bring flowers with the words, ‘I love yellow flowers and the Master white ones. Ask Kishori (Swami Parameshwarananda) to bring both kinds of flowers.’ Having secured the flowers from the Swami, Nareshchandra ran back to find the Mother still standing at the former place. In accordance with a faint hint from the Mother, he offered the white flowers at her right foot and the yellow ones at her left and then he said passionately, ‘Mother, I offer you all the results of all actions here and hereafter. ’ By accepting his worship that day of her own accord, the Mother disclosed indirectly to him the truth of the unity of

Siva and Sakti in her holy person. That is why she wanted the white flowers for the snow-white Siva as identical with Sri Ramakrishna and the yellow ones for the golden-coloured Sakti as embodied in herself.

But if she explicitly asserted this unity in special cases, it is not to be inferred that she promulgated it as a dogma for the acceptance of all her disciples, though as a matter of fact, the Hindu background of most of them led them to believe this without being told so. In the case of the sceptics, instead of asking them to believe outright, she waited patiently. To a monastic disciple she said after initiation, showing him the Master’s picture, ‘He is the guru.’ The disciple asked, ‘Mother, you assert that the Master is the guru; what are you then?’ The Mother replied, ‘My boy, I am nobody—the Master is the guru, and he is the chosen Deity.’ In another case, on the contrary, as soon as the Mother said pointing to the Master’s picture, ‘This is your guru,’ the disciple added, ‘Yes, Mother, he is the guru of the Universe.’ And when she said pointing to the image of Bhavatarini, ‘This is your chosen Deity’, the disciple asserted, ‘Mother, why should I go for an unseen entity, when I have one before my very eyes?’ In other words, when it was possible to worship the Universal Mother in Her form as the Holy Mother, there was no need for him to take the help of an image. The disciple’s insight and sincerity pleased the Mother, who said, ‘Very well, my boy, let it be so.’ She laid a little emphasis on the word, ‘so’.

But though she was very outspoken when talking with sincere souls about her identity with the Master, any suggestion of eliminating the Master and installing herself in his place militated against her whole outlook. Any mention of this pained her intensely. When a disciple said in answer to an inquiry, ‘Mother, with your blessing, I am quite well,’ the Mother at once admonished him saying, ‘Why do you drag me in everywhere? Can’t you mention the Master’s name? All that you see belongs to the Master. ’

The truth is that such a rebuff was evoked only when there was an undertone of differentiation between the two to the disadvantage of the Master. Riveting his attention on this fact of the identity of the two souls, Swami Premananda declared one day, with the greatest fervour, that those who would make any distinction between them, would fail to achieve anything in spiritual life, since they were but the obverse and reverse of the same coin.

Two devotees went one day to pay their respects to the Mother at the ‘Udbodhan’, where a third person also happened to be present. The Mother took three leaves on which she arranged some prasada of the Master; and then touching each share slightly with the tip of her tongue, she handed them over to the three visitors. At this the third person blurted out, ‘Mother, I don’t take anybody’s prasada except the Master’s.’ The Mother replied impassively, ‘Then don’t eat.’ A little later, the gentleman’s doubts cleared up and he said with delight. ‘Mother, now I have got it; you are the same as the Master—identical.’ With the same serenity the Mother again said, ‘Then eat.’

The Master comes down in every age and his Sakti, the divine Mother, accompanies him. She often pointed out this eternal relationship to the chosen few. Nalini Sarkar of Midnapore asked her once, ‘Mother, did you come with all the incarnations?’ ‘Yes, my son,’ replied the Mother.

When the Master comes to us again, his retinue will follow, and his Sakti, the Mother, will again incarnate, though this is by no means a happy development to contemplate. In the course of a conversation Gauri-Ma said one day (February 9, 1912) at the ‘Udbodhan’, ‘The Master said that he would come down again twice; once in the form of a

baul.–’ The Mother confirmed her by saying, ‘Yes, the Master said, “You will have in your hands (my) hubble-hubble.” The Master will have a broken stone vessel in hand. Maybe, the cooking will be done in a broken iron pan. He walks on and on—neither looking to the right nor left. ’

Ashutosh Roy, a devotee of Ranchi, had a vision of the Master, by whom he was called at night; and after opening the door he found the Master standing on the road with ochre cloth, wooden sandals on his feet, and a pair of tongs in his hand. A disciple reported the incident to the Mother at Jayrambati, in May 1913, and asked, ‘Mother, why did he see him with wooden sandals on his feet and a pair of tongs in his hand?’ The Mother replied, ‘That’s the outfit of a monk. For has he not said that he will come in the trappings of a baul? In the attire of a baul—with a long robe, matted hair on the head, and beard so long. He said, “I shall go home by way of Burdwan; somebody’s son will be easing himself on the road; in my hand will be a broken stone vessel, and a bag dangling under my arm.” He will be walking on and on, and eating all the time—without looking in any particular direction.’ The questioner asked, ‘Why the Burdwan road?’ The Mother replied, The home lies that way.’ Again the question was put, ‘Is he a Bengali then?’ The Mother said, ‘Yes, a Bengali. Hearing him I said, “How strange, my dear! What a strange fancy you have!” He smiled and said, “Yes, you will have my hubble-hubble in hand.”’

Being told that the Master would again incarnate together with his companions and associates, Lakshmi Devi, his niece, swore, ‘I will not be coming again even though I be chopped to pieces like tobacco leaves.’ At this the Master replied with a smirk, ‘Where will you be if I come away? You will be ill at ease. It’s like a float of (the interlocking aquatic plant) Kalmi; if one pulls at one end, the whole mass moves.’ The Mother, too, disliked the idea. At Vrindaban, when the Mother and the devotees had alighted from the train and Golap-Ma was reaching out their belongings from inside the compartment, she found the hubble-bubble of Latu (Swami Adbhutananda) lying in a corner. So she took it up and handed it over to the Mother. At once Lakshmi Devi twitted the Mother saying, ‘There you have already taken in hand the hubble-bubble.’ The Mother, too, said, ‘Master, Master, here I have finished holding the hubble-bubble,’ and she dropped it instantaneously to the ground with a thud.

The Mother told the disciples, ‘He (the Master) said that he will live for a hundred years with his children.’ According to her, the golden age began from the advent of the Master. He came with some extraordinary souls as his esoteric circle. For instance, the Master himself told her that Swami Vivekananda belonged to the group of the great seven seers of old and that Arjuna came as Swami Yogananda. Ordinary people are born and they die; but these highly gifted and illuminated souls accompany an incarnation to advance his mission. About their extraordinary spiritual calibre, she said ‘All those who came earlier have come again.’ And to her hearers she spoke with pride about the devotees of the inner circle, ‘Don’t you notice how childlike is Rakhal’s (Brahmananda’s) behaviour? Even now he is like a little boy. And look at Sarat (Saradananda); what a lot of work he does, how many difficulties he shoulders, and yet he never complains. He is a holy man; why should he be doing all this? If they want, they can keep their minds fixed on God day and night. It’s only for your sake that they continue on a lower plane. Keep their characters before your eyes, and serve them’ She considered these direct disciples of the Master as her own sons and said, ‘Rakhal, Sarat, and others — all of them issued out of my very body. ’ From a very remarkable statement about the Master’s life as a whole it seems as though in the Mother’s estimation the three phases in the Master’s life — his Lila (play) as an incarnation, his spiritual practices, and his mission after realization — could be arranged in a graded scale. Of these, the first seemed to occupy the pride of place and last came his mission. An incarnation plays out of the fullness of spirit and every word or movement of his is calculated to stir up similar underlying emotions in gifted souls. Here there is no motive, but only living inspiration for others. In the second phase of spiritual practices, his movements seem to be more concretely correlated to, and circumscribed and determined by, his environment; and hence though his divine glory cannot find free play here, the very fact of conformity to human standards makes his life more widely appreciated. In the third phase of encompassing the general weal, all kinds of human factors intervene to shut out and refract the inner light; and here, though his divinity becomes deeply overlaid with humanity, his real mission as the incarnation of the age is more widely fulfilled. On these matters the Mother said one day to Swami Keshavananda, ‘I tell you, my son, it never occurred to me that he practiced all the religions with the express motive of preaching the idea of spiritual harmony. He was always in his mood of divine ecstasy. He practiced all the methods through which the Christians, Mohammedans, Vaishnavas, and others worship God and realize truth, and thereby he tasted God’s disports in diverse ways. Days and nights passed by him without any notice. But what you should note, my dear, is that renunciation is his special message in this age. Did any one see such natural renunciation any time before? As for the harmony of religions you speak of, that also is true. In previous incarnations, all other spiritual moods looked insignificant because of the emphasis on a particular one.’ The truth revealed is higher and more fundamental than either its method of realization or its subsequent promulgation and application. On another day she said to a second devotee, ‘Men are ever forgetful of God. And hence, whenever the occasion demands, He comes down now and then to show the way to the worldly by following it Himself. This time He showed renunciation. ’ In fact, no attempt at world-regeneration can succeed unless it has selflessness as its basis; and without it the realization of God can never be dreamt of.

1. Sri Sri Latu Maharajer Smriti-Katha

(p. 278), Sri Sri Sarada Devi (p. 56), Sri Ma (p. 81), which slightly differ in

2. Baul is derived from the word vatula, meaning crazy. The hauls are a community of god-intoxicated mendicants who sing mystic songs to the accompaniment of ektara, an one-stringed musical instrument. They wear long robes often torn to pieces and almost touching the feet; and they do not pay heed to social customs and fineness of manners.

Leave a reply