Life

ON THE COMMISSION

Gradually it became clear after the Mother’s arrival at Dakshineswar that the Master, by imparting transcendental as well as secular wisdom, by deepening her life of divine aspiration, and awakening her dormant power of spiritual ministration, was preparing her for taking up and fulfilling the mission that had just commenced in his own life. We have read of the invocation of the deity at the Shodashi worship, when the Mother received the adoration of the great awakened soul and became conscious of her own divinity, though she did not even then decide whether or not to take up what was to be her life’s work. Moreover, that worship took place at dead of night in a closed room. The people probably heard of this long afterwards, but they could not grasp its full import. Now came the time for a clearer call to the Mother to enter into her own domain and to bear witness before the devotees as to her real stature. And hence we find that during the closing years of the Master’s life, his work in this field followed a well-defined course. He had been trying to arouse her sub-conscious potentiality through veneration, adoration, and direct references to her divinity. He had been equipping her mind for her future task of guiding spiritual aspirants by teaching her various powerful mantras, pulsating with the life he had breathed into them through his own experiments with them, and telling her of the levels of life for which each mantra was suitable. And he had been creating a field for the expression of her motherhood and vivifying it by introducing his devotees to her and telling her how to deal with them. And as a last step he invited her off and on, in no uncertain terms, to cooperate in the task willingly and at the same time he apprised the devotees of the course of future development. We shall now proceed to a study of these events.

Before we do so, however, we must be careful about one thing; we must not commit the blunder of thinking that the Holy Mother’s present-day glory is entirely due to the Master’s training and endeavour. It is a basic truth of the art of teaching that unless a student has some latent powers of a very special or high order, the best teacher and the most valuable instruction cannot make him surpass the ordinary run of mankind. And along with those powers is necessary the willing and eager cooperation of the taught. But the Mother was willing even in those early

Dakshineswar days to make the Master’s effort a success, just as the Master, fully cognizant of her essential divinity, was extremely eager to make her begin her mission.

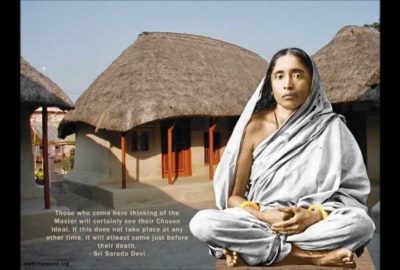

The Master one day told Golap-Ma, ‘She (Mother) is Sarada, Saraswati1; she has come to impart knowledge. She has descended by covering up her beauty this time, lest unregenerate people should come to grief by looking at her with impure eyes.’ On another occasion he said, ‘She is the communicator of knowledge, she is full of the rarest wisdom Is she of the common run? She is my Sakti (power).’ And to his nephew Hriday, he said, ‘My dear, her name is Sarada, she is Saraswati. That’s why she likes to put on ornaments.’ The reader may have in mind that when the Holy Mother came to her father-in-law’s house as a child and began crying at the sight of her person denuded of ornaments, Chandramani Devi, mother of Sri Ramakrishna, placed her on her lap and consoled her saying that Ramakrishna would adorn her afterwards. The Master had that scene ever before his eyes, and accordingly told Hriday, ‘Just see how much money you have in your safe. Have a pair of gold armlets made for her.’ The Master was then ill; still he ordered those armlets to be made at a cost of three hundred rupees. But the actual cost came up to two hundred rupees only, and so the balance was paid to the Mother in cash. When the Master had been going through his austerity in the early days, he had a vision of Sita at Panchavati when he noticed that her bracelets had diamonds cut on their surface; hence he had such bracelets too, made for the

Mother1; and then he humorously remarked, ‘That’s my relationship with her.’

It was not easy to recognize the Mother, behind her rural simplicity, lack of modern culture, and absence of pelf and power. Sri Ramakrishna himself knew that the modern world, rolling in wealth and steeped in enjoyment, could not easily appreciate a character that was made up of the purest material and had nothing of the flash and flourish which appeal to a modern mind; and hence he spoke about the Mother in fun, ‘She is a cat under ashes.’ As the true colour of a cat covered with ashes escapes the notice of a careless observer, so also does the true stature of the Holy Mother elude the ken of ordinary men. Swami Premananda wrote about her in a letter: ‘Who has understood the Holy Mother? There’s not a trace of grandeur. The Master had at least his power of vidya (knowledge) manifested, but the Mother?—her perfection of knowledge is hidden. What a mighty power is this! Glory to the Mother! Glory to the Mother! Glory to the powerful Mother! A poison that we can’t assimilate we pass on to the Mother. She draws everyone to her lap. An infinite power—an incomparable grace! Glory to the Mother! Not to speak of us; we haven’t seen the Master himself doing this. With how much caution and what testing he accepted any one! And here—what do you see here at the Mother’s place? Wonderful! Wonderful! She grants shelter to everyone, eats food from the hands of almost anyone, and all is digested! Mother, Mother, victory unto the Mother!’ And the world-renowned Swami Vivekananda wrote: ‘Brother, I shall demonstrate the worship of the living Durga, and then shall my name be true.. Brother, I tell you, I am a fanatic in this matter. Of Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, you may assert that he was God, man, or whatever you like; but fie on him who is not devoted to the Mother.’ When we read such invaluable appreciations, our pen suddenly stops and in bewilderment we ask ourselves, ‘Are we not engaged in a task entirely beyond us?’ And yet once we are in it, we have to proceed with the Mother’s grace as our only strength.

Before proclaiming the divinity of the Holy Mother at Dakshineswar, the Master hinted at it at Kamarpukur, though the uneducated and uncultured village women did not, perhaps, comprehend her greatness. The Mother was then a mere girl of fourteen. When the Master talked to the village women of higher things, the Mother often fell asleep. The others then tried to wake her up and said, ‘What a pity; she misses these fine things! She has fallen asleep!’ But the Master said, ‘No, my dear, no; don’t awaken her. Don’t think she is asleep without reason. If she hears these things, she will fly headlong away. ’ The women later reported this to the Mother. The Master alone knew what he exactly meant by those words. Probably, he wanted to convey the idea that the Mother’s mind had such an innate repugnance for this world and was ever so attracted towards transcendental verities, that if she became engulfed in such high thoughts before an adequate environment was ready for the divine part she was destined to play, the very purpose of her birth in this world of ours would be frustrated.

Howsoever that might have been, this much will suffice for the present as an introduction to the comprehension of her divinity. As we proceed further in the delineation of this unique personality we shall find that though her character evolved wonderfully amidst strange surroundings, it reached perfection in one particular field. Though she was divine, the world has seen in her an all-loving Mother. This is a very important phenomenon in human history. In the Srirama-purva-tapani Upanishad (verse 7) it is said, ‘For fulfilling the purpose of the aspirants, the formless

Brahman assumes forms.’ In the Gita (IVll) Sri Krishna declares, ‘In whatsoever way men approach Me, even so I reward them’ And in the Chandi (XII.35) the Rishi (Seer) says, ‘O King, that Divine Mother, though birthless, yet manifests Herself again and again for the protection of the world. ’ And hence from time immemorial men, particularly Indians, have been worshipping Her in diverse symbols and images. Her hymns and songs too, are innumerable. She is with us under various guises and in multifarious forms. She bestows wealth and wisdom. She removes ailments and grants health, and She affords us protection and kills our enemies. When pleased, She grants faith, devotion, and even emancipation; but when offended She liquidates the sin and the sinner. We have been adoring Her from time of yore in Her aspects as women, as sources of inspiration, as divinity, or as mothers. Drawn by the devotion of mortals She comes down now and again. We meet Her in the person of a Sati, Sita, Radha, or Andal1. A pathetic cry from a helpless child like the poet-mystic Ramprasad makes Her leave the heavenly throne and come down as a small girl to help the devotee in mending his dilapidated fence. In the forms of daughters and mothers She consoles Her devotees in their trials and tribulations. Men have thus established the sweetest of relationships with the Transcendental

Entity. And yet the Devi still remained in Her lofty aloofness as ever. In spite of brief appearances for granting the desires of particular devotees, or Her descent with the Lord as Sita or Radha, She did not incarnate fully as the Universal Mother for bringing about a world regeneration through Her personal endeavour. In the life of the Holy Mother we arrive at the culmination of this line of descent. The deity here is fully recognized as a living human personality receiving the worship of Sri Ramakrishna and being identified by him with Mother Kali in the temple and his mother Chandramani Devi in the Nahabat.

Why did man want the Devi in this particular form and why did She grant the prayer? We have stated that unless the Devi incarnated as the Mother, there would ever have remained a gap in the spiritual world. Man comprehends higher and newer truths in terms of what he already knows. The mother holds the child in her womb and suckles it after its birth. On opening the eyes, the child finds the mother as a sure and the most unique source of all affection, nourishment, happiness, beauty and security. In the field of spiritual striving, too, the aspirant wants to visualize the Deity as the embodiment par excellence of all those fine human relationships. Sri Ramakrishna said, ‘The attitude of looking on God as Mother is the highest

form of spiritual discipline.’ Swami Vivekananda eulogizes motherly love thus: ‘The position of the mother is the highest in the world, as it is the one place in which to learn and exercise the greatest unselfishness. The love of God is the only love that is higher than a mother’s love; all other love is lower.’ (The Complete Works of Swami

Vivekananda, Edn. VIII, Vol. I, p. 66.) If it is the aim of the aspirant to merge the sense of ‘I and mine’ in the universal ego of the Deity, and to taste the bliss of consciousness through unquestioning dependence and refuge in that one reality, then in the motherhood of the Deity lies the guarantee for such a consummation. Through the different attitudes of quietude, service, and sonship to God, we do of course get an increasingly greater degree of intimacy with Him; but the absolute self-absorption of the unquestioning child, perhaps, transcends even this.

And the aspirant wants that the Lord should, through His mercy, forgive all his weakness and inability and draw him to His lap with the fullest affection; he wants to be assured of his future by visualizing in the face of his Deity this dear and dependable smile of affection. From childhood he is used to this kind of assurance; why should he be deprived of this in the field of spiritual advance? The selfless guru, out of his compassion, imparts to the disciple the knowledge of higher things, whereby he can withdraw his mind from the enjoyment of worldly things. The infinitely glorious Deity, endowed with the best of all qualities and transcending the lapses and limitations of life, holds before the aspirant an unsurpassable ideal whereby he is inspired and energized to attain that state. The ever-loving and ever-smiling Mother melts the heart of the child with a touch of affection, wipes away from his mind all traces of past failures and dejection, and exerts an irresistible pull whereby he gets dissolved in an ocean of bliss and freedom from cares. Furthermore, in this transparently pure attitude of the aspirant, there is no room for any bad thought; and there is no touch of selfishness and meaningless emotionalism. This figure of the Mother, shining in Her self-collected poise and compassion is absolutely without a parallel. The aspirant, sitting fearlessly in Her lap or holding on to Her apron, can easily get across this wilderness of the world. God’s incarnation as Mother was necessary for fulfilling these needs. And above all, it was necessary for the Deity to come down as the Holy Mother, so that the present sensuous and materially-minded world might be raised to a higher state of aspiration and experience. Humanity is, therefore, fortunate today in having this living and life-transforming Motherhood in a concrete form and in intimate touch with all the ramifications of life.

The Master was aware of this significance of the Mother’s life and he apprised her of this. Subsequently, when an inquisitive disciple of the Mother asked her, ‘Mother, other incarnations survived their Saktis (consorts)1; but why did the Master precede you this time?’ The Mother said in reply, ‘My boy, you must be aware that the Master looked upon all in the world as Mother. He left me behind for demonstrating that motherhood to the world.’ On another occasion she said, ‘When the Master departed, I too felt like going away. But he appeared and said, “No, you stay on; there’s much still to be done.” In truth, I find at long last that there’s much to do. ’ One day at Cossipore the Mother noticed the Master looking at her for a long time, as though wishing to say something. And she said at last, ‘Why don’t you speak out what you wish to?’ The Master said in an aggrieved tone, ‘Well, my dear, won’t you do anything? Should this (pointing to his own body) do everything single-handed?’ The Mother, conscious of her helplessness, said, ‘I am a woman. What can I do?’ The Master at once corrected her, ‘No, no, you’ll have to do a lot.’ When the Mother slipped down from the stairs at Cossipore, thereby spraining her ankle, she took rest barely for three days out of sheer necessity, and then, impelled by an extreme desire for service, she went up the Master’s room with his food. Finding the Master reclining with his eyes closed, she said, ‘It’s time for your diet; get up.’ The Master seemed to have returned from some far-off land and while still in that mood of aloofness, he said, ‘ See, the people of Calcutta appear to be crawling about like worms in the dark. Do look after them’ The Mother pleaded, ‘I am a woman. How can that be?’ The Master pointed towards his body and continued in the same strain, ‘What after all has this one done? You’ll have to do much more.’ The Mother wanted to change the topic and said with some emphasis, ‘That will take its own time. Do take your food now.’ Then the

Master sat up.

Even before this, the Master used to sing:

To whom to explain the difficulty I courted by coming here?

The wearer best knows where the shoe pinches

How can others know?

A maid am I in a foreign land Where I blush to show my face.

I can’t state, can’t explain What a handicap it’s to be a woman.

And at the same time he told the Mother, ‘Is this my trouble alone? It’s yours too.’ The Master did not rest content with reminding her of her real nature and inviting her openly to shoulder the responsibility; he also presented his devotees to her and thus created a field for the expression of her latent motherhood. At the time of sending young Sarada (Swami Trigunatitananda) to the Mother for initiation he quoted a Bengali couplet to put faith in him:

Infinite is the maya of Radha which defies definition—

A million Krishnas and a million Ramas have birth, and live, and die.

The Mother did not certainly initiate Sarada on that day, for she herself declared Swami Yogananda to be her first disciple, and his initiation took place at Vrindaban years after this. But

Sarada’s brother, Sri Ashutosh Mitra, maintains that the Mother initiated him Perhaps, the Mother gave him as well a mantra after she had done so to Yogananda. Be that as it may, for the present we are not studying the Mother’s reaction, but rather the Master’s efforts at inducing her to active ministration.

With the growth of the Master’s circle of devotees the Mother’s domestic duties in the form of cooking, preparing betel rolls, etc., began to grow apace. Just then Latu had come to Dakshineswar to live with the Master. At first he spent most of the day sitting at Panchavati and other places made holy by the Master’s austerity. One day when the Master was proceeding to the tamarisk grove he noticed the Mother kneading. the dough and a little further on he saw Latu in his meditation. He at once called the young man and said by way of correcting his mood, ‘Hullo Latu, you are sitting here, and she over there can’t get anyone to make bread out of the dough!’ Then he conducted Latu to the Nahabat and said, ‘This boy is very pure of heart. When you have need of anything tell this boy; he will do it for you.’ From that day Latu became a member of the Mother’s family.

When Rakhal, the spiritual child of the Master, came to Dakshineswar, the Master introduced him to the Mother; and when Rakhal’s wife came, he sent her to the Mother with the instruction, ‘Let her (Mother) see her daughter-in-law’s face after giving her a rupee.’1 At the Master’s direction Gopal-dada did all the marketing for the Mother and Yogin helped her in various other ways. When Puma, as a boy, began frequenting Dakshineswar, the Mother was one day asked to feed him As desired by the Master she dressed the boy with garland and sandal paste and then sat by him-to feed him most affectionately with the various dishes she had cooked for him After the meal she poured water on his palms for washing his mouth. All this time the Master kept on pacing the small distance between the Nahabat and his room He approached the Mother and gave some instruction as to how Purna was to be treated, then he walked away; but before he had gone far, some fresh idea occurred to him and he retraced his steps to communicate it to the Mother. Thus it went on till the end. As for the Mother, it seems that through this endearing contact with Puma, she had not only her motherly love partially satisfied, but she also learnt how to worship a boy as Narayana.

The Master always took pains to establish abidingly sweet relationships among the devotees and the Mother. When his devotee Balaram Babu’s wife fell seriously ill, the Master told the Mother, ‘Go, visit her.’ The Mother was used to long walks and a distance of about five miles from the Kali temple to

Balaram’s house was not at all too long for her to cover on foot. But then, part of the way lay through the thickly populated city, and the Mother’s sense of propriety told her that it would not be commendable for the Master’s wife to be seen walking in the streets of Calcutta; and hence she said, ‘How am I to go? There’s no conveyance.’ The Master replied, ‘What! You won’t go when my Balaram’s family is facing disaster? You will walk; go on foot.’ But the Mother had not to walk; for a palanquin was hired and she went in it to the devotee’s house. It may be added in passing that during her stay at Shyampukur she visited Balaram’s ailing wife once again on foot, and that of her own accord.

There is a funny incident suggestive of the Master’s witty way of getting his own ideas expressed and executed through the medium of other people. Gauri-Ma was then a constant visitor to Dakshineswar, and she sometimes spent the night with the Mother at the Nahabat. One day the Master went there and asked her in the Mother’s presence, ‘Tell me, Gaur-dasi (Gauri-Ma), whom do you love more, me or her.’ That sprightly lady avoided a direct answer and with a view to adding to the gaiety of the situation, sang in a sweet voice:

You aren’t greater than Radha (your sweetheart), O Flute player (Krishna),

People in danger call on You as

Madhusudana;

But when it’s Your turn to cry, You make Your flute call, ‘O thou Radha, thou young maid. ’

The meaning of the song was very clear. The Mother pressed Gauri-Ma’s hand in sheer shame, and the Master left smiling in utter discomfiture.

We get another illustration of a similar nature from the Sri Ramakrishna Punthi (pp. 353-355). One day Sri Kalipada Ghosh’s wife came to the Master with a sorrowful face and a heart full of distress to tell her tale of woe. Her husband had fallen into bad company and was bringing ruin on the whole family; if the Master could prescribe some remedy, she would be saved from a life of torment. Kali Babu had not visited the Master up till then; and the people of Calcutta had not as yet come to recognize in the Master a prophet of the highest spiritual order who was absolutely free from any show of supernatural powers. Not knowing much of this unsullied saintliness, the lady wanted some kind of charm from him. This was galling to the Master, but for some reason best known to him—it might have been through sheer fun, or real pity for the lady or some inscrutable design—he did not dismiss her outright, but advised her to go to the Nahabat saying, ‘There’s a woman there. Tell her everything without reserve, and she will give you the real remedy. She knows such mantras and charms, and in this matter her power is greater than mine.’ The Holy Mother was then at worship with her mind soaring in a domain of extreme compassion. She heard the woman with full sympathy, but did not do anything forthwith; for it appeared to her that the Master was only having a little fun. And yet unwilling to disappoint such a distressed soul, she said, ‘What, after all, can I know, my child? In truth, he knows the charm; do go to him’ Finding the woman returning, the Master perhaps concluded that the fun had worked; accordingly, to add more zest to it, he sent her again to the Nahabat. When the lady had thus been tossed between the Master and Mother thrice, the Mother took pity on her. She did not want to reduce the whole affair to a merry joke, thus adding insult to injury. Accordingly, she consoled her and taking a bel leaf out of the offerings made to the deity, handed it over to her saying, ‘Take this with you, my child; this will fulfill your desire.’ The lady received the leaf with the greatest reverence and took leave of the Mother. In due course Kalipada Ghosh’s mind took a turn for the better, and by stages he became one of the staunch followers of the Master. Through this small incident the Master made the Mother open out her heart in practical benevolence.

Thus, as days rolled on, the Mother was becoming consciously or unconsciously more and more intimately associated with the Master’s mission of spiritual regeneration, though the mode of expression of her infinite power was naturally orientated by her predominant mood of motherliness.

A yearning for children is deep-rooted in the hearts of women. In most cases, motherhood centres on one’s own children, thus making it indistinguishable from selfishness. In some cases other children, too, are associated with one’s own, when motherly love takes the form of philanthropy. Sometimes, though rarely, this affection transcends physical relationships and expands over the whole of creation, thereby rendering divine the life of the mother. Even more rarely it comes down in the form of spiritual inspiration in the life of a godly woman who remains absolutely untouched by the world, and whose words and acts open up all closed hearts and lead them Godward. But the motherhood with which we stand face to face in the life of Sri Sarada Devi is of a higher order, being coextensive with Divine love, and hence truly unique and incomparable. And yet from a rational point of view there is a gradation in its manifestation; and a rational comprehension presupposes an analytical study of it in stages. But while we try to grasp its working on any particular level, we must not lose sight of the basic unity running through this life as a whole, in the light of which alone these stages have to be traversed.

When and how was this pure and selfless yearning for divine motherhood first kindled in the recesses of the Mother’s heart? Perhaps she had it in her to the fullest extent even before she was aware of it. This is the natural psychological process. As a matter of fact, we noticed that in her girlhood she attended on her younger brothers, and helped to cool by fanning the food served to famished people. Events of a similar nature have forced themselves on our attention when studying her relations with the devotees at Dakshineswar. But here we are thinking more of the conscious rise of that sentiment and its operation, rather than its hidden working.

She heard her sympathetic friends condemning all childless women as unfortunate and inauspicious. Her mother too lamented at times thus: ‘To what a mad son-in-law have I married my daughter! Alas, she has no family life, no child, and does not hear any one calling her “mother”.’ The Master one day heard this and said, ‘Dear mother-in-law, you need have no disappointment on that score. Your daughter will have so many children, you will see in the long run, that the distressing call of “mother” will make her bewildered.’

The Master’s prophecy apart, the Mother herself related how, by constantly listening to others, the craving for children woke up in her heart: ‘I heard, ever and anon, both here and at Kamarpukur, that a woman, unless she has become a mother, is not fit for any (auspicious) work. A barren woman cannot take part in any auspicious work. I was very young then. These words set me thinking sorrowfully, “Of a truth, should even a single son be denied me?” When I went to Dakshineswar, the question once arose in my mind. When I first had the thought I did not tell anybody; but the Master said spontaneously,’ “Why do you worry? I shall leave you such jewels of children as one can hardly get even if one performs the severest of austerity, to the extent of cutting off one’s head. You will find in the end so many children calling you ‘mother’, that you will be unable to manage them all.”’

Women have been cherishing this desire for children in their hearts from time immemorial. True it is that the Mother had some taste of this motherhood even during the lifetime of the Master; but that did not satisfy her infinite yearning. The Mother herself has spoken of her feeling of disappointment: ‘When the Master departed, I thought in solitude—I was then at Kamarpukur —“I’ve no son and nothing else; what will be my lot?” One day the Master appeared and said, “Why do you worry?

You want one son—I have left for you all these jewels of sons. In time many will call you mother.”’ The Master talked of things lying in the womb of futurity. But at present we are studying how far this longing of the Mother and this assurance of the Master bore fruit when the latter was still in the world.

The Mother treated the young devotees at Dakshineswar as her own children and felt a strong affection for them When the need arose, she could protect them more tenderly than even a mother could or did. A crazy woman used to come to the Master at Dakshineswar. At first all took her to be merely insane and so treated her kindly. Afterwards it turned out that she belonged to that class of spiritual aspirants who consider God as their sweetheart. As she identified Sri Ramakrishna with God, she mentally developed that peculiar attitude towards him As contrasted with this, the Master regarded all women as veritable manifestations of the Universal Mother. Without considering seriously the consequences of such a contradiction, the crazy woman ventured one day to speak out her mind to him. As a reaction to such an antagonistic sentiment, the Master was thrown so violently into a fit of childlike protest that he jumped up from his seat instantaneously, his cloth dropped down from his loins, and he began to pace the room like a madman, cursing such a relationship in the strongest terms he could muster. The Mother heard all this from the Nahabat. Feeling humiliated by this insult to her daughter, she said to Golap-Ma, ‘Just look at this! If she has been unthinking in her talk, should he not have sent her to me? What’s the meaning of abusing her like this?’ She sent Golap-Ma at once to call the crazy woman to her, and when the woman came, she said affectionately, ‘My daughter, you may as well not go to him, since your presence irritates him; you can come to me.’

In those days, many of the young devotees spent some nights at Dakshineswar practicing spiritual disciplines under the Master’s guidance.

As overeating hinders concentration of mind, he kept a strict eye on their regimen, and instructed the Holy Mother to give Rakhal six chapatis, Latu five and Gopal-dada and Baburam four each. The Mother, however, could not tolerate this kind of limitation to her own field of motherly care; and hence she gave to each according to his need, much in excess of the Master’s prescription. One day the Master discovered on inquiry from Baburam that he got five or six chapatis at night, and that the Mother was responsible for this. He accordingly went to her and tried to impress on her that she was spoiling their future by her heedless affection. But the Mother protested saying, ‘Why do you get upset because he had just two more chapatis? I shall look to their future. Don’t you take them to task for this matter of eating.’ The Master said nothing by way of reply, but in his mind he saluted that all-conquering motherliness and left the place with a smile. He must have been delighted that day to find the Mother consciously entering on her future field of activity.

From Yogin-Ma we learn that the Mother welcomed the women devotees with the utmost affection and this pleased the Master. When that devout lady went to Dakshineswar for the first time, the Master came to learn that she was going without any food; and so he sent her to the Nahabat saying, ‘There’s some rice and vegetables inside; go and have your food.’ The Mother hurriedly placed before her all that was available —rice, luchi,1 vegetables, etc., and fed her with great care. That first meeting ripened into intimacy, so much so, that when a few days later the Mother got into a boat to cross the Ganges for going to Kamarpukur to be present at her nephew Ramlal’s marriage, Yogin-Ma kept on looking as long as the boat could be seen and then began to weep. The Master found her in that state and consoled her. When the Mother returned, he told her, ‘That girl with big eyes who comes here, loves you very much. The day you left, she wept at the Nahabat.’ The Mother said, ‘Yes, her name is

Yogen.1’ The Mother had so much affection for and faith in Yogin-Ma that she consulted her at every turn. After Yogin-Ma had dressed her hair, the Mother would not untie the chignon for three or four days together and would say, ‘No, it was dressed by Yogen; I shall untie when she comes again.’

Yogin-Ma, one day, noticed the Mother putting spices in some betel rolls, while others were prepared without them. Curiosity impelled her to ask, ‘Mother, why did you not put cardamom and other spices in these? For whom are those meant, and for whom these?’ The Mother replied, ‘Yogen, these (the spiced ones) are for the devotees; I have to make them my own through love and care. And those are for the Master; he is already my own.’

There was then a constant flow of devotees and religious singing in groups or singly was the order of the day. The Mother who had consecrated her life for the service and happiness of the Master, and consequently of the devotees, had no rest. Cooking went on day and night. And yet in the midst of all this, her mind was ever at the feet of the Master. Owing to this incomparable concentration of mind, she seemed to know the Master’s thoughts even before he opened his lips, and she arranged accordingly. Sarada, Purna, and others might not have the money to return to Calcutta either because of poverty or because their guardians were opposed to such visits. Therefore, the Master directed them to take the necessary money from the Mother. The fare from the Baranagore bazar to Beadon Square in Calcutta for a seat in a hackney carriage in those days was one anna. The Mother knew that Sarada needed money since he had to come surreptitiously eluding his father’s vigilance. So whenever Sarada came she kept in advance a one anna piece on the steps of the Nahabat for him to find at the time of departure. As soon as she heard the Master telling Narendra on his arrival, ‘You will stay here today,’ the Mother at once began boiling gram and preparing chapatis, for Narendra liked thick chapatis with gram soup. When the Master came to instruct the Mother about Narendra’s food, he found that he had been anticipated. If women devotees came to Dakshineswar late in the evening, it became a problem for the Master to accommodate them during the night. Knowing as he did that the Nahabat was a cramped place, he used to ask them to sleep on the covered terrace outside his room; but the Mother assured them that there would be sufficient space for them in the Nahabat itself. The devotees had their food at the Nahabat and then went to the Master for a little talk. On returning to the Nahabat they found to their amazement that single-handed the Mother had cleaned up the whole place and spread beds for all. Moreover, she drew them all to her side so cordially that they felt no need to go elsewhere.

In this way, the great desire of the Master to give shape to his message on the one hand, and the deep affection of the Mother for her children on the other, combined to attract her more and more to the field that was eminently her own. Through this joint effort, too, the inner circle of devotees of the Mother was selected even in those early days. We have already referred in passing to some of her young sons who became monks afterwards. We have also on occasions referred to Yogin-Ma and Golap-Ma who were the Jaya and Vijaya1 of the

Holy Mother in the present incarnation. We shall refer to some more interesting and illuminating incidents about these two devout souls before we pass on to other topics.

After the Master went to Shyampukur for treatment, the Mother, left behind at Dakshineswar, was passing her days in great sorrow and anxiety. Just then Golap-Ma happened to tell Yogin-Ma casually in the course of a talk, ‘It strikes me, Yogen, that the Master left for Calcutta because he was angry with the Mother. ’ When the Mother came to learn of this from Yogin-Ma, she could not control her tears. She at once proceeded to Shyampukur in a carriage and asked the Master, ‘Is it true that you have come here because you are angry with me?’ The Master replied, ‘No, who told you so?’ ‘Golap,’ replied the Mother. The Master flared up at this and said, ‘Is that so? Did she make you cry by saying so? Does she not know who you are? Where is Golap? Let her come!’ Fully consoled, the Mother came back to Dakshineswar. When Golap-Ma next appeared before the Master he reproached her saying, ‘What’s this that you said to make her cry? Don’t you know who she is? Go at once and beg her pardon. ’ Golap-Ma forthwith walked to Dakshineswar and with tears in her eyes said, ‘Mother, the Master is very angry with me. I said it all in sheer thoughtlessness.’ The Mother made no direct reply, but with a laugh she patted Golap-Ma’s back thrice saying, ‘O dear Golap!’ Golap-Ma’s heart was instantly lightened.

When Golap-Ma first went to Dakshineswar, she was overwhelmed with grief for her only child, a daughter, named Chandi. The Master received her warmly and after more intimacy told the Mother: ‘You should feed her (Golap-Ma) to her heart’s content; if the stomach is full, the sorrow will be assuaged.’ On another occasion he told the Mother, ‘You should take care of this brahmin girl (Golap-Ma). She it is who will be your constant companion.’ Needless to say that the Mother accepted her with open arms, and Golap-Ma too, took up her position as the Mother’s maid from that very time. There were slight differences of temperament between the two as we have noticed but they did not ever so slightly ruffle the surface of their lives,—so intimately bound to each other did they become.

We now turn to Yogin-Ma. When the Master was ill at Cossipore, she longed to go to Vrindaban for practicing austerity, and she informed the Master accordingly. At this his face brightened up and he said encouragingly, ‘So you want to go to Vrindaban! It’ll be excellent. Do go there; you’ll find everything there.’ The Mother was then present in the room with his diet. He turned his eyes to her and asked Yogin Ma, ‘Did you tell her? What does she say?’ ‘Whatever was to be said has been said by you already,’ intervened the Mother. ‘What is there to add?’ The Master did not seem to heed this, but advised Yogin-Ma again, ‘My dear child, go after obtaining her consent— you will get everything.’ Unmindful of this, the Mother picked up the empty bowl and started going downstairs. Yogin-Ma followed her.

Next morning Yogin-Ma came to Cossipore to take leave before starting on her pilgrimage. After making her obeisance to the Master she went to the Mother to bow down to her. The Mother then laid her hand on Yogin-Ma’s head and as a blessing made japa of her mantra, counting it on her fingers. Two days later Yogin-Ma went to Vrindaban and took shelter in Kala Babu’s Kunja (grove) on the Yamuna, which belonged to Balaram Babu’s family and which was dedicated to a deity that received their regular worship.

1. Sarada means Saraswati, the mythological goddess of Learning; and etymologically Sarada means ‘the giver of sara or essence’, i.e., knowledge of Brahman.

1. Yogin-Ma says, ‘At that time the Mother lived at the Nahabat like the most revered Sita. She wore a piece of cloth with broad red borders, and vermilion at the parting of their hair. Her thick black tresses almost touched her knees. She wore a gold necklace, a big nose-ring, ear-rings, and bracelets, those which Mathur Babu gave the Master when he took to spiritual practice by assuming the role of a handmaid to the Divine Mother. ’

1. Sati and Sita were consorts of Siva and Ramachandra respectively; and both of them were noted for their unparalleled devotion to their husbands. Bhu-devi, consort of Vishnu incarnated in South India as Andal (or Kodai), illustrating the madhur bhava (looking upon God as one’s nayaka or husband).

1. This is not strictly correct. The questioner perhaps meant that the Saktis of the incarnations did nothing tangible after the incarnations bad passed away.

1. It is an old Hindu custom.

1. Flat pieces of cake made with flour and fried in clarified butter.

1. The Mother called both Swami Yogananda and Yogin-Ma by the same name Yogen; and to distinguish between the two she often added son or daughter before the name.

1. Jaya and Vijaya are the two maids of the Mother of the Universe. The Holy Mother sometimes referred to Golap-Ma and Yogin-Ma as her Jaya and Vijaya.

Leave a reply