Life

IN HER HUSBAND’S COTTAGE

The Holy Mother stayed at Balaram Babu’s house for about a week and then went to Kamarpukur. Before starting for the place, she visited Dakshineswar to bow down before all the deities and have another look at everything associated with the Master. Swami Yogananda, Golap-Ma, and some others accompanied her up to Kamarpukur.

They went to Burdwan by train, from where they walked the rest of the way for lack of money. The first phase of their journey from Burdwan to Uchalan, a distance of about sixteen miles, tired out the Mother very much, and she felt hungry. At Uchalan, Golap-Ma managed to cook a little khichudi on tasting which the Mother said, ‘O Golap, what a delicacy you have prepared!’ Swami Yogananda and others left for their places after staying at Kamarpukur for a few days. Then began the Mother’s sorrowful life at that village, during which time she was practically alone, as she had none to sympathize with her or even to talk to her, barring some two or three old acquaintances.

When during the Master’s illness at Cossipore, his nephew Ramlal came to see him one day, the Master told him, ‘You will serve Bhavatarini (Kali at Dakshineswar), and so you will not lack anything? He then turned to the Mother and said, ‘You will live at Kamarpukur, and look after Lakshmi1 a little. You will not have to provide for her food; but see that she does not leave home to go elsewhere! The devotees will have as much veneration for you as they have for me.’ To Ramlal, again, he said, ‘See that your aunt stays at Kamarpukur.’ Ramlal replied, ‘She will stay wherever she wills.’ The Master easily saw through the meaning of that statement, and he reproved him saying, ‘How is that, my boy? Why have you been born a man ?’ Lakshmi Devi had been to Vrindaban with the Mother, but she did not go to Kamarpukur, preferring to live with her brothers at Dakshineswar. As for Ramlal, he not only refused to shoulder any responsibility for the Mother, but also created a tremendous difficulty for her. Trailokyanath Vishwas, son of Mathuranath and grandson of Rani Rasmani, granted a small allowance of seven rupees for the Mother. But during her stay at Vrindaban, Ramlal dinned it into the ears of the cashier of the temple that the devotees of the Master were looking after her, and that there was, therefore, no need for an allowance from the temple. So that contribution was stopped.1 Swami Vivekananda and others argued against such a step, but to no effect. When the Mother heard of it, she said with extreme indifference, ‘If they have stopped it, let them have their way. When even the Master is gone, what shall I do with money?’ The devotees of the Master had decided that they would contribute ten rupees a month for the maintenance of the wife of their guru. But that pious wish did not materialize. Hence the life of the Mother at Kamarpukur was not only solitary, but also one of privation.

Sri Ramakrishna once said to her, ‘You will stay at Kamarpukur; you will grow pot-herbs, eat your rice with greens, and call on Hari.’ This was not an order, but it was a wish of the Master, a hint of a means of her livelihood. As though to fulfill those words, the Mother had to follow that very pattern of life in those days. There were times when she boiled some rice, but had no salt to savour it with. When after some days the state of affairs at Kamarpukur became known in Calcutta, the devotees took her there. But that was long after. In the meantime the Mother continued to suffer, without even informing anybody, in the very mud hut which the Master had bequeathed to her; for even then was ringing in her ears that counsel of the Master, ‘Mind you, don’t put forth your hand to anybody even for a dime. You will have no lack of coarse food and cloth. Once you put forth your hand for a dime from any one, you sell your head to him . . .Even living on charity is preferable to living in other people’s houses. Even if any one of the devotees should offer to keep you in his house with love and respect, you should not give up your own home at Kamarpukur. ’ Let us for a moment stop here to look around the Kamarpukur of those days. The Kamarpukur of the boyhood days of the Master must have changed a good deal with the change of time, as is quite natural; still the village did not, in all probability) appear new to the Mother’s eyes, though there is a world of difference between the Kamarpukur of the later part of 1887 and the

Kamarpukur of today (1954). To the south of the Master’s house at that time, and contiguous to it, was the house of Shuklal Goswami, known popularly as the Gosain-mahal, which looked something like a land-holder’s office establishment with high brick walls around and a brick house in the middle. Near the present well south of the Master’s temple was the entrance of the Gosain-mahal which opened to the road on the west. South of the mahal was a small pond on whose bank was the memorial of a suttee of the Pyne family. Further south was the guest house of the Lahas. East of the dwelling house of the Lahas, in the centre of the village, is a big pond called the Kamarpukur (tank of the Kamars), on the south-west corner of which the Kamars (lit., black-smiths) still live. Dhani Kamarni, who acted as the midwife at the birth of the Master, was born among these people. North of the Master’s house is the big pond called the Haldar-pukur or the tank of the Haldars, who no longer live in the village, but have shifted to other places. In the Mother’s time the two storeyed brick house of the Lahas was still habitable and the family was well off. Near the Master’s house there were many sweetmeat sellers and starting from the north-eastern corner of the house up to the market place there were rows of shops on either side of the main village road. The Dome (sweeper) quarters along the road, to the north-west of the Master’s house, had not been vacated then. And the Yugis (weavers) still had their homesteads between the Master’s house and the Haldar-pukur, and they still conducted worship at their Siva temple. The mango grove of Manik Raja had not been denuded, and the tall palm trees still reflected themselves on the calm and transparent waters of the tanks and ponds scattered everywhere.

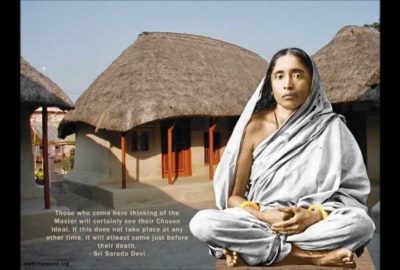

The Master’s homestead then consisted of three mud houses for dwelling purposes, with thatched roofs, standing in a line on the southern side of the village road running from east to west. The house on the east, outside the courtyard, served as a parlour. The house in the middle, which was the largest and over which another storey was raised later, was used by Rameshwar, the elder brother of the Master. The westernmost house was used by the Master, and in this was spent the Kamarpukur phase of the life of the Mother. Between these two dwelling houses was a small door leading to the northern road. At right angles to the Master’s bedroom was the shrine of Raghuvira built of mud and straw. The kitchen house along the southern boundary wall had three rooms, one of which was used by the Mother. In the middle of the eastern wall was the entrance to the court-yard. Along this wall, between the entrance and the kitchen was the husking shed where the Master was born.

The altar of Raghuvira and other deities that existed in those days was built by the Master’s father Kshudiram Chattopadhyaya with earth carried by himself on his head. At present there are four deities—the image of Gopala installed by Lakshmi Devi, the white stone emblem of Rameswara Siva brought by Kshudiram from Rameswar, the Raghuvira stone which he got in a dream and a pitcher filled with water, painted with vermilion, and holding mango leaves on its top, which represents the goddess Sitala. About Sitala the Mother said, ‘She, indeed, is our family deity. I heard it related how my father-in-law saw in a dream that the Great Mother, in Her form of Sitala—a little girl with a robe red as vermilion, was sweeping away all calamities, all the refuse, with brooms in her hand, and holding a pitcher at her waist, sprinkling ambrosial water with the (mango) leaves, thereby bringing peace to all beings by removing all cares.1 Sitala is only one of the aspects of the Great Mother; that’s why there’s that pitcher painted with vermilion and containing water for bringing about peace. The water is changed on special days.’ The Mother also stated that Raghuvira was the same as Ramachandra whose birthplace was in the north-west; and so the Master’s father offered him khichudi to suit his north-western taste.

Kamarpukur was then a flourishing, populous, and busy village; and because it was so, it frightened the Mother, full of modesty as she was. Moreover, these people without culture, without liberal ideas and sympathy, remained unmoved at the helpless condition of this widow, and at the same time they lacked any curiosity for imbibing higher ideas from her. It was natural, therefore, for her to be faced with many problems. She continued to wear her bracelets, in obedience to the bidding of the Master. But the rural critics, unmindful of such a vision, became increasingly vociferous; and she took these away from her hands. Her second problem was, how to live so far away from the Ganges, a love for whose holy waters was ingrained in her. We saw her going on sacred occasions with village women to the Ganges for a dip, not to speak of her stay on its bank at Dakshineswar for a long thirteen years. Such maladjustments made her a little nervous, and she thought she would one day go for a bath in that river again. Just then she saw the Master approaching along the road in front, followed by Narendra, Baburam, Rakhal, and other devotees. From his blessed feet gushed forth a stream of water which moved before him in waves; and so she thought, ‘I see that he himself is everything; from his blessed feet springs the Ganges!’ Hence she plucked handfuls of red china-roses from near Raghuvira’s shrine and laid them as an offering on the waters of this Ganges. Then the Master told her, ‘Don’t remove the bracelets from your hands. Don’t you know the Vaishnava Tantra?’ The Mother replied, ‘What is Vaishnava Tantra? I know nothing of it.’ Gaur-dasi will come this afternoon,’ said the Master, ‘you will hear from her.’ That very afternoon came Gauri-Ma, who explained to the Mother with the help of the Vaishnava scriptures how there can be no such thing as widowhood for her, since her husband’s body was not material but spiritual; furthermore, she was none other than Lakshmi herself, the goddess of fortune and the consort of Vishnu. For her to be without ornaments would mean the deprivation of the whole world of its good things.1 Later on, when Yogin-Ma went to Kamarpukur, the Mother while describing that incident to her added, ‘The Master then stood at the foot of yonder peepul tree. I saw at last the Master disappearing in the body of Naren…Eat the dust of the place, bow down.’ When this news traveled from mouth to mouth and reached Swami Vivekananda, he said that it would have been better for him not to have heard of the entry of the Master into his body. However that might have been, one cannot but note that the incident made a tremendous impression on the Mother’s mind about the mission of the Master and the sanctity of Kamarpukur. She got over the fear of idle gossip and put on the bracelets again; and her cloth also continued to have a thin red border instead of being wholly white. These she never discarded till the end.

The rural critics too became silent. Such problems like these agitate most the womenfolk, and the solutions also emerge from them. When hostile gossip about the Mother reached the ears of Prasannamayi, daughter of the village landlord, Dharmadas Laha, who had been a widow from early life and was respected by all around for her virtue and wisdom, she folded her hands respectfully and touching her forehead with them in token of salutation, said, ‘Gadai (Ramakrishna) and Gadai’s wife —they are divine.’ The scurrilous women of the village never afterwards opened their mouths.

Although the two problems of the Mother, viz., wearing of ornaments and living near the Ganges, were thus solved, the other complicated ones defied solution for sometime. Soon after she came to the village, she sought the help of Prasannamayi and Dhani Kamarni for securing a companion to be by her side. Prasannamayi gave her the assurance: ‘As to that, my dear, you need have no anxiety; my maid-servant will sleep with you at night.’ If the maidservant failed to turn up, Dhani’s sister Shankari slept in her house at night, and one of their brothers helped her at odd jobs. Prasannamayi always looked after her needs, and the Mother too relied on her for advice. Prasannamayi then lived in the Gosain-mahal. She was very devotional in temperament and liked to look after the comforts of guests and brahmins. So she and the Holy Mother spent long hours in talking over religious matters.

In spite of this casual help and oral sympathy, the Mother still felt very lonely and unsafe. She was well prepared to spend her days by tying her worn-out cloth in a hundred knots, digging the earth with a spade, and growing pot-herbs for her food; but over the uncertainty of the future, family differences, and social indifference and oppression, she had no control whatsoever. True it was that from the psychological point of view she was quite free from such fears after the Master’s vision, as she herself said, ‘Then, as I began to have visions of the Master, that fear gradually subsided.’ These visions again, were intimate. One day the Master appeared and said, ‘Feed me with khichudi.’ The Mother thought that as Raghuvira was identical with Ramakrishna, though they differed in form, it would be enough to offer the khichudi to the former. She did so, thinking all the while in a spiritual mood that the Master himself was having his meal. But despite this spiritual sublimity, the environmental antagonism continued just as before and caused not a little anxiety.

The question crops up here, ‘When the Mother was in these circumstances, what were her people at Jayrambati doing?’ We know that they were not particularly well off. Her mother, Shyamasundari Devi, was having a very hard time. Still, when she heard of her daughter’s distress, she sent her son, Kalikumar, to Kamarpukur to bring her to Jayrambati. But the Mother refused to go just then. When she did go after some time, Shyamasundari could not check her tears at the sight of her extreme poverty. We like to fancy that this visit was during the annual Jagad-dhatri worship, for which the Mother had an innate attraction and as such, would not have liked to miss the occasion. Shyamasundari Devi took this occasion to hold her back, but the daughter replied, ‘Now, I am going to Kamarpukur, Mother. Afterwards it’ll be as He ordains.’

In the course of a short time, a great change came over the Kamarpukur family. The Mother’s nephews, Ramlal and Shivaram, and her niece, Lakshmi Devi, then lived generally at Dakshineswar, though they very often came to their village home to stay there for short periods. We have noted that Ramlal (or Ramlal-dada) was somewhat indifferent towards the Mother. But this cannot be said about Shivaram or Shibu-dada, as he was generally called. Shibu-dada received from the Mother his first alms after his investiture with the sacred thread, and so he regarded her more as his god-mother than as an aunt and the Mother too treated him as a son. Long after, when the Mother was permanently residing at Jayrambati, Shibudada sat for his lunch at Kamarpukur one day; but when he had half finished, the desire grew in him to eat something from his god-mother’s hand; and so he walked to Jayrambati and after having been fed by Holy Mother returned to Kamarpukur with a betel in his mouth given by her. We have many such instances of the Mother’s affection for all of them.

Once during this period, Lakshmi Devi and many others were present at Kamarpukur. Till then the family was a joint one. But as misfortune would have it, the family was broken up by partition. Lakshmi Devi was a Vaishnava by temperament. Sometimes she sang Vaishnava songs inside the house with a sweet voice, which attracted people of a similar faith. The Mother could not be quite easy about this. She remembered that when Lakshmi Devi sang in this way before the Master, imitating fully the gestures and postures of professional singers, the Master, while enjoying it, was amused; but he warned the Mother, ‘That’s Lakshmi’s temperament; don’t you tread on her footsteps and throw your modesty to the winds. Besides this difference, the divergence of outlook in daily talks and actions between the Holy Mother and the rest of the family became more pronounced as days rolled on. The Mother preferred to spend the rest of her days peacefully in the thought of the Master, while around her others swirled the currents and cross-currents of the world into whose vortex they wanted to draw the Mother as well. The Mother remained unperturbed and unruffled, never uttering a word of protest. But the Chatterji family did nothing to avert the split that is usual under such circumstances. Thus, despite the passivity on the one side, the aggressiveness on the other threw the

Mother out of the main body. One day, on her return from Jayrambati, the Mother found that Ramlal-dada had left for Dakshineswar with the others after making some arrangement for the daily worship of Raghuvira. To her share had fallen the little cottage of the Master; she entered therein determined to keep up its sanctity.

On a study of the Mother’s life we come to learn that commencing from her arrival at Kamarpukur in September 1887, she lived there for about nine months (up to April, 1888), after which the devotees brought her to Calcutta. From Calcutta she again went to Kamarpukur in February next and lived there almost for a similar period. Most probably, the subsequent periods of her stay there were never so long, though she came to live there quite a number of times.1 It is not possible to determine definitely the time of various incidents that took place during those periods of stay. In the account so far presented, we have made no attempt to date the incidents exactly; and in what follows, too, we shall not try to do more than indicate the dates in a general way.

During the Mother’s stay at Kamarpukur, the visits from the devotees were few and far between. Of course, most of them were too poor to undertake the pilgrimage; but the few who went there were received heartily by the Mother, for the meetings of persons that are akin and familiar were always delightful. Such visits rather relieved the monotony of her otherwise dull village life. But all visits were not welcome; on the contrary, some were a source of trouble. Once at least, the Mother had to face such an embarrassing situation. Harish, a devotee of the Master, was a constant visitor at the first Math of the Ramakrishna Order at Baranagore, and this frightened his wife. With a view to counteracting this tendency to renunciation, she surreptitiously applied drugs and charms, which brought about a certain derangement of his mind. While still under the influence of those drugs, Harish visited the Mother at Kamarpukur. The Mother could at once see through the mind of the man and hence wrote to the Math to take him away. Accordingly, Swamis Saradananda and Niranjanananda started for Kamarpukur. But before they could reach there, Harish’s lunacy grew out of control, and the Mother had to devise her own remedy for this. We present the incident in her own words:

‘At this time Harish came and stayed at Kamarpukur. One day, I was returning from a neighboring house. As I stepped into the courtyard, Harish began chasing me. Harish was not in his senses then; his wife had drugged him and madness had followed upon it. There was nobody else in the house; so where could I escape? In a hurry, I began circling round the barn of paddy (near the Master’s birthplace). But he would not give up the chase. After going round for seven times, I could run no longer. Then I stood firm working myself up to my full stature (lit., assuming my own form). And then, placing my knee on his chest and taking hold of his tongue, I slapped him on his cheeks so hard that he began to gasp for breath. My fingers became red. ’

It is difficult now to ascertain in what sense the Mother used the words ‘my full stature.’ Many believe that, since the Mother was an incarnation of the Mother of the Universe, it was possible for her to assume all kinds of divine forms and attitudes; and in the present context, she became Bagala to punish with heroic hands the demon in

the person of Harish.1 There is no reason why a devotee should not believe this; but even a matter-of-fact man will be surprised to see how the Mother, who was noted all along for her modesty, meekness and mercy, could at a critical moment be on her mettle. When we look more closely into such incidents of her life, it strikes us that the poet who penned the line in the Chandi, ‘Of all beings in the three worlds (heaven, earth and hell), in You alone, O goddess, is seen a kindness of heart combined with heroism in fight,’ was truly a seer. That punishment cured Harish not only for the time being. Later he fled to Vrindaban on the arrival of Swami Niranjanananda, and there became fully normal after some time.

One winter morning, in the beginning of 1888, Krishnabhavini Devi, wife of the great devotee Balaram-Babu, and her mother Matangini Devi, came to the Master’s birthplace from Antpur with a brahmin girl and a faithful man as escort. As devout Hindus they knew that their guru’s household, and that of a brahmin too, should not be burdened on any account, and hence they placed sufficient money in the Mother’s hands for making a suitable offering to Raghuvira, whose prasada only they would eat. The Mother made suitable arrangements for their comfort, and on the fourth day she took them to Jayrambati, where, too, they spent three nights and then left for Calcutta by way of Kamarpukur1.

In the midst of fear and poverty, the Holy Mother kept burning the lamp of her spiritual ministry. It was probably during her second stay at Kamarpukur. There lived a monk from Orissa in a cottage attached to the outer wall of Gosain-mahal, inside which dwelt Prasannamayi who looked after the monk’s needs. He had incurred the displeasure of some hot-headed and well-connected young men of the locality, so that he was on the point of leaving the village, when the Mother came to his help. The monk commanded the respect of the common folk; and thus with their help she proceeded to build for him a cottage at the south-west corner of Haldar-pukur. The rainy season was then imminent and the sky looked threatening. Hence the Mother prayed fervently with folded hands, ‘O Lord, kindly forbear, kindly forbear! Let his thatch be completed and then You can pour as much as You like.’ After the monk had been given a place to lay his head in, the Mother used to supply him with his foodstuff, though she had hardly sufficient for herself; and inquired of him every morning and evening, ‘Father monk, how are you, dear?’ But the monk did not live there for long; for, as Providence would have it, he expired soon in that cottage.

Though the Mother was in extremely indigent condition in the beginning, matters improved a little in course of time. The devotees, coming to know of her difficulties, organized what help they could. In addition, her share of the land at Shihar, left as a trust by Master in the name of the family deity, and the Lakshmi-jala land which came down from the Master’s father, Kshudiram, as a heritage, yielded sufficient paddy not only for herself but also for some charity. Towards the end of the period we are discussing now, there was a maidservant named Sagarer Ma (Sagar’s mother) who helped the Mother in her domestic work. From her it has been gathered that she used to do the shopping for the Mother. A portion of whatever the Mother cooked at noon, she kept in a pot for Sagarer Ma, and when the woman came, she handed it over to her saying, ‘Put this in your mouth first and drink some water, and after that begin your work.’ During the three days that the goddess Durga is worshipped annually in Bengal, special worship was done and offerings made to Sitala by the Chatterjis at their Kamarpukur house. Brahmins were fed on this occasion. When the time for the feast came, the Mother used to say, ‘Shibu (Shibu-dada), you spread the leaf-plates and serve salt and water, while I serve rice on all the leaves for the brahmins.’

Sagarer Ma further says, ‘Hers was the store of Lakshmi (goddess of wealth), as it were; nothing ran short. Whatever surplus there remained, she lovingly gave away to us the next day. ’ Over and above all this, the Holy Mother fed a number of guests.

We have noticed the Mother’s diligence at Dakshineswar, Shyampukur and Cossipore. At Kamarpukur too, the same assiduity was in evidence, rather it increased because of the manifold responsibilities she was burdened with. She got together all that was necessary for cooking food, cooked it, and offered it to Raghuvira with all punctiliousness. If Shibu-dada happened to be at Kamarpukur he performed the worship, otherwise somebody else did it. Before the daily worship commenced, the Mother finished her bath in the Haldar-pukur and started cooking on two ovens, and this was finished before the sun moved away from the verandah (i.e., before noon), it being unbefitting to offer food to the deities after mid-day.

Of a truth, the Mother tried her best to follow the Master’s wishes—she was ready to wear herself out at Kamarpukur through toil, tears, privation, and disease. But there is a limit to endurance whether physical or mental. Where the environment is wholly unhelpful or antagonistic, one with a sense of selfrespect cannot continue spiritual practices long in a course of strenuous adjustment and compromise. Differences of outlook were there to be sure; in addition, the moral and spiritual atmosphere of the village was unbearable for her. The way in which the influential young men of the village misbehaved towards the monk from Orissa, disregarding the intervention of such a venerable lady as Prasannamayi, set the Mother thinking much about her own future. And on top of all this came the insistent calls from her children in Calcutta, which ultimately proved too strong for her affectionate heart. Ultimately, Kamarpukur ceased to be her main place of residence. This does not, however, mean that she neglected her husband’s bequest; it only means that she took up her task in a wider and more effective sense. And though she did not permanently stay at Kamarpukur, she spent money for the proper maintenance of the Master’s cottage. If any devotee went that way, she reminded him of its sanctity and advised him to spend the night in it, so that he might imbibe some of its holiness. She helped her nephew Ramlal with money in putting a new storey over their own dwelling house. And she bestowed particular care on the worship of Raghuvira and spent money for the purpose.

Her latter-day disciples were curious for details about her leaving Kamarpukur and plied her with various questions. One devotee asked her, ‘Mother, you don’t so much as visit the Master’s house; when you come to the village from Calcutta, you go straight to your father’s house. Are you, in this, treading in the footsteps of your predecessors?’ The Mother laughed heartily and replied, ‘Not so, my son! Can I forget the Master’s house? Shibu is my god-son. But the Master is now no longer in the physical body; I am pained if I go there. That’s why I don’t go.’ The irremediable pangs of separation was there to be sure, but to that were added the external maladjustments owing to the antagonism, negligence, and inequities of the people around her, of which she seldom spoke as it hurt her to expose others’ faults. On rare occasions only she opened out her mind a little. To a boy devotee who attended on her, she said, ‘When after the Master’s passing away I moved about here and there for sometime and then went to live at Kamarpukur, my relatives seemed to be indifferent towards me. And coming to learn of the high-handedness of the villagers, my mother brought me here (to Jayrambati); she did not allow me to live at Kamarpukur any more. From that time on I have been living with my brothers through stress and strain. And now, again, they complain, “She does not look after us.” The human mind is strange indeed. ’

1. She became a widow soon after marriage and stayed in her father’s house at Kamarpukur.

1. The Holy Mother said: ‘Trailokya used to give me seven rupees. After the Master’s death, Dinu, the cashier, and all others conspired to stop that money. My relatives, too, who were there, treated me as an ordinary mortal and joined with them.’ (Udbodhan, V)l. XXVII, pp. 11-12). See also Sri-Sri Lakshmimani devi.

1. In Bengali ‘Shital Karchhen’, making cool or removing the heat. Sitala is feminine of Sital. Sitala is generally the goddess of pox or similar calamities; but the Mother here gives the word a higher meaning, equating Sitala with the Universal Mother.

1. Some Bengali books, for instance, Gouri-Ma (pp. 110-12) place this incident at Vrindavan. But the Mother recounted it as we have presented it (vide Sri Mayer Katha,

part II, p. 148).

1. From the notes of Master Mahashaya we gather that she lived at Kamarpukur during the following periods: End of October 1890; February, and July to October 1891, July of 1892, January and July of 1893; 13th May 1895; November 1895 to January 1896; May, and Durgapuja days (September-October) of 1897.

1. Vagala is one of the ten Mahavidyas, forms of the Great Mother. In that form she killed a demon in the very same way as the Mother punished Harish.

1. The incident had an important bearing on the Mother’s subsequent life. It can be inferred that, though the Mother tried her utmost to hide her poverty and helplessness from the devotees, their loving eyes penetrated into the truth; and therefore, after their return to Calcutta they told the other

devotees all these facts. As a result the Mother was soon brought to Calcutta. The other version is that uncle Prasanna, who then lived in Calcutta, divulged the facts to Ramlal, Golap-ma, and others, and thus the devotees were stirred to action. In any case, Golap-Ma took a leading part in this matter.

Leave a reply