Life

BEREAVEMENTS

Nilmadhav suffered from asthma, which became unendurable sometimes. Soon after his return from Puri, the disease became so acute that it defied treatment, and he was bed-ridden. Unmindful of her own health, ease and rest, the Mother nursed him day and night, helped by some of her own attendants. But about two months after his return from Puri, his condition became very bad; and everyone was apprehensive of the worst at any moment. Once the Mother finished the worship of the Master and the offering of food to him expeditiously and came down. Then everybody pressed her to have her meal first, assuring that nothing would happen to her uncle in the meantime. The Mother hurried through her meal and then rushed to the patient. But now everyone sat silent around the patient. With great anxiety she cried out, ‘Is my uncle no more?’ Who could answer? The Mother’s face then looked flushed with anger and repentance at the thought that she had failed to be there at the last moment just because she listened to the foolish persuasion of others. With extreme bitterness she said, ‘Why did you send me to eat that dirty stuff? I missed a last look at my uncle!’ And she began sobbing like a little helpless girl who had lost her father.

When she had composed herself a little, she asked an attendant to sit near the dead body while she herself went up to bring some leaves and flowers that had been offered to the Master. These she placed on the head and chest of the body and at both the places made japa with her hand. Then came the time for taking out the body for cremation. Of the bearers three were brahmins and another a non-brahmin. Golap-Ma noticed this unorthodox arrangement and drawing the Mother’s attention said, ‘Why should a sudra touch the dead body of a brahmin?’ The Mother replied, ‘Sudra? Devotees do not belong to any caste.’ The cremation took place duly at Kashi Mitra’s Ghat; uncle Prasanna performed the last rites (April [?] 1905).

Uncle Prasanna then lived in a tiled cottage on the Simla Street. His eldest daughter Nalini had been married at a very early age, in the beginning of January, 1900, soon after the birth of Radhu. The bridegroom was Pramathanath Bhattacharya who belonged to Goghat in the Hooghly district of Bengal. With uncle Prasanna lived his wife, two daughters—Nalini and Maku—and Pramatha. Pramatha fell ill at this time and the disease was diagnosed as double pneumonia. The Mother kept herself informed about Pramatha’s condition and often visited him

The doctor in attendance was still a young man; but owing to some family misunderstanding he had become very morose and had lost all interest in life. To relieve his mind of extreme depression, he took morphia, frequently injecting it into his body at regular intervals. One day an attendant of the Mother, who was also a friend of the doctor, took him to the Mother who had that day gone on an invitation to Master Mahashaya’s house at Jhamapukur along with some devotees. When the doctor and his friend arrived, she was in the shrine, where the two were directed to proceed. The doctor had come out only with a loin-cloth on a sudden call from his friend, thinking that something was wrong with Pramatha which required his immediate presence. He had also finished his lunch. Therefore when the friend proposed on the way that he should have his initiation from the Mother, he was rather surprised and pleaded his handicap. But the friend argued that it would be better to leave the whole matter in the hands of the Mother who best knew what formalities were essential before initiation. So the doctor entered the shrine and explained everything to the Mother. Still the Mother initiated him with a mantra. That produced a tremendous change in him His whole face became radiant, the black tinge at the corners of his eyes disappeared, and his mind was filled with a new light. That day he sat again at lunch with all the devotees, and forgetting caste prejudices and thinking himself to be as good a son of the Mother as any other, shared the same food with his friend, who belonged to a lower caste. Noticing this, the Mother remarked that they looked like two sons of the same mother, to which they added, ‘That’s true enough, Mother; for we are your sons.’ The mental condition of the doctor improved so much in course of time that he got over his misunderstanding and mental suffering, set an example to other devotees by whole-heartedly serving the Mother and the monks of the Ramakrishna Math and helping in the work of the Ramakrishna Mission.

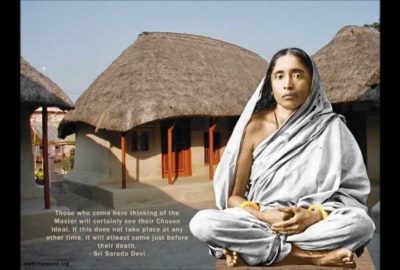

Some photographs of the Mother were taken during her residence at the Baghbazar house. Some of these were taken at the studio of Shri B. Datta of Chitpore Road, in the beginning of April, 1905. In one of these the Mother sits amidst Sister Lakshmi, Nalini, and Radhu. Swami Virajananda had another picture taken next month at Messrs. Van Dyke’s on the Chowringhee in which the Mother sits with two plants in pots, one on either side. The picture of the Mother that is worshipped nowadays and is the most well-known was taken much earlier at the request of Mrs. Ole Bull in 1898, when the Mother lived in the Bosepara Lane house. At that time Sister Nivedita and Golap-Ma attended to the hair and clothes of the Mother according to their own taste.

Besides the doctor, another devotee named Sri Lalit-mohan Chatterji came to the Mother at this time. When he had become very intimate with the devotees and had known the Mother for some time, he became eager to be initiated by her. The Mother accordingly went to his house at Chhutarpara and gave the mantra to him and his wife. Lalit Babu also became a very sincere friend of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission and made his own life a real success by serving’ the Mother in various ways.

Binodbehari Som, a student of the school where Master Mahashaya taught, was introduced by him to the Master who influenced him very much. But subsequently Som entered a theater and took to drinking under the influence of which he talked desultorily when returning home at dead of night. He knew Swami Saradananda intimately and used to call him his dost (chum). His friends nick-named him Padmabinode. Now, Padmabinode, when passing by the Mother’s house on his way home from the theater, used to call on his dost, who, however, instructed everyone neither to respond nor to open the door, lest the

Mother should be disturbed. One night, getting no answer from inside the house, Padmabinode started singing under the influence of liquor:

Get up, Mother gracious, and open the door;

Nothing is visible in the dark; and my heart ever throbs.

How often do I call on thee, O Tara (Kali) at the pitch of my voice!

And yet, though kind thou art forsooth, how thou behavest today!

Leaving thy child outside, thou sleepest inside;

While crying, ‘Mother’, ‘Mother’, am I reduced to skin and bone!

With proper pitch, tune, modulation, and cadence in all the three gamuts,

I call on thee so often; and still thou awakest not!

Maybe, thou hast turned thy face because of my engrossment in play. Do thou look at me with upturned face, and I shan’t go for play again. Who but a Mother can bear the burden of such a wretched son?

The plaintive appeal of the song was irresistible. The blinds of the Mother’s window went up at once, and then the window itself opened wide. Padmabinode noticed this and said with delight, ‘Have you got up, Mother? Have you heard your son’s call? Since you’ve got up, take this salute.’ So saying he began to roll on the street. Then taking the dust from the street and putting it on his head he went away singing another tune,

Keep Mother Shyama (Kali) carefully concealed in your heart;

O mind, mayst thou and I only see Her, and none else.

and he repeated with some gusto,

May I see Her, and not my dost.

Next day the Mother inquired about him, and learning everything, remarked, ‘See, how firm is his conviction!’ Padmabinode saw the Mother in that very manner at least once again. Next morning, when her attendants remonstrated that it was not proper for her to leave her bed at that unearthly hour, she replied, ‘I can’t contain myself at his call.’

Not long after, Padmabinode had a severe attack of dropsy, and he had to enter a hospital. During his last moments he expressed a desire to hear the Bengali Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, which was read out to him Tears trickled down the corners of his eyes as he heard the blessed words, and he passed away into eternal silence with the Master’s name on his lips. The Mother heard all this and said with evident satisfaction, ‘Why should this not be so? Was he not the Master’s son? He was wallowing in mud, and has now returned to the lap to which he belonged. ’

The Mother’s return to Jayrambati was fixed for Jyeshtha (May-June) of 1905. This was her first journey by way of Vishnupur, where she and her party alighted from the train and had their lunch at a small wayside shop. Then Brahmachari Krishnalal, who had accompanied them, started back for Calcutta, while the others got into four bullock-carts in the evening. Next morning they reached Kotulpur where they cooked and had their lunch at noon. Then the Mother and Radhu got into a palanquin which followed a shorter route to Jayrambati while the others continued in the carts by a longer one via Shihar.

The Mother had not been at Jayrambati during the Jagad-dhatri worship in the previous year; and hence the celebration this year was on a grander scale. Swami Saradananda sent there all the requisites, and the Mother added grace by her presence, and solemnity by her silent prayer.

One incident of this period shows how humble in spirit the Mother was, and yet how much esteemed she was by the local people. One day, when Sri Ganesh Ghoshal of Kamarpukur, who had been a class-mate of the Master, came to visit the Mother, she proceeded to bow down before him in all reverence; but Sri Ghoshal protested vehemently that it would be very harmful for a son to be saluted by his mother; and he himself fell down on his knees and saluted her.

At the end of 1905, Brahmachari Girija (later Swami Girijanarida) went from Kankurgachhi to Jayrambati with his friend Batu Babu. He was a candidate for initiation and had obtained the Mother’s permission previously. When they arrived at noon, the Mother said ruefully, ‘My sons, my eldest sister-

in-law- has got an attack of cholera. Just at noon she had cooked and fed the servants, and then suddenly fell into the grip of the disease.’ Uncle Prasanna was then in Calcutta. There was neither medicine nor a doctor in the village. And so, in the course of twelve hours, the aunt died. Her daughters Nalini and

Maku were still very young, and had none to look after them. The Mother, who had given shelter to Radhu earlier, now took these two girls also under her care.

Brahmachari Girija now thought that, under such tragic conditions, propriety demanded his keeping silent over the question of initiation; hence wishing to spend the time otherwise, he approached the Mother for her permission to go out for a visit to the Goddess Vishalakshi of Anur with whose name the childhood days of the Master were associated. The Mother said, ‘With what expectation you must have come! Finish your bath and then come. Let me tell you something at least. ’ Most graciously she initiated him that very day. Batu Babu had no idea of taking any initiation just then; but the Mother blessed him also with a mantra.

And now came the month of Magha (January-February) of 1906, when the winter in Bengal is very cold. In the morning many sat on the terrace in front of the Mother’s room. The previous day was the market day at Shiromanipur from where a woman had purchased vegetables for sale at Jayrambati. She came today, and grandmother Shyamasundari bought from her some greens and vegetables in exchange for paddy, mustard seeds, etc. Then the grandmother felt somewhat out of sorts. Nevertheless she helped in husking paddy. Soon she felt so weak that she lay down under the porch of uncle Kali’s house and called out to an attendant of the Mother, ‘Brother, I feel I am dying; there is a reeling sensation in the brain.’ The attendant was alarmed and called the Mother there; but none could believe that the old lady was really going to breathe her last so soon. The Mother and the attendant did all they could under the circumstances. The old lady said, ‘I have a desire for pumpkin curry.’ The Mother assured her that she had not to worry about such a trifling thing, which would be arranged when she recovered. But grandmother said that the opportunity would never come and that for the time being she wanted a little water to drink. The Mother hurriedly brought some Ganges water and put it thrice into her mouth. Then the grandmother’s body became motionless. The Mother knew that the last moment had come and so made japa with her hand on her head and breast. Then Shyamasundari Devi quietly passed away. It was nine o’clock in the morning. The whole household broke into a mourning wail. Uncle Varada, who was in the field, hurried back home on getting the news; and then the body was cremated on the bank of the Amodar.

The virtuous lady Shyamasundari Devi had been blessed by having had the Mother of the Universe in her womb. The Holy Mother once said, ‘My father was a great devotee of Rama, and a generous soul. And how kind was my mother! That is why I was born in this house.’

In the beginning, grandmother, like others, used to think of Ramakrishna as an eccentric. But as days rolled on, this notion was replaced by an indescribable sentiment of affection mixed with awe. Grandmother loved the Master’s children dearly. She stocked a good variety of rice and other eatables in anticipation of their coming; and said, ‘My Sarada (Swami Trigunatitananda) may come any day, and Yogen (Swami Yogananda) may come; all these things are necessary.’ She also added, ‘So long as I am here, there’s Brahma, there’s Vishnu, there’s the Universal Mother, there’s Siva—all are here. When I depart, they too, will go. For who else can possibly take care of them? Mine is a household of God and godly people.’ The grandmother’s love embraced all the little children of the village. Even on the last day of her life, she played with her grandchildren —the little ones of the village—for a very long time.

Grandmother departed from the body fully conscious, with her blessed daughter Sarada by her side. But the Holy Mother wept bitterly like any mortal child. She was motherless now; in fact she had none else to whom she could look up for a bit of affection. Father, husband, uncle, mother,—all had left her one by one. And worse still, her Yogananda, on whom she could depend, was no more; and Abhay, whom she loved dearly, had come to an untimely end. The responsibility now thrust on her shoulders was indeed very heavy. Her sorrow today knew no bounds.

Yet the world has its own norm; and time runs its course relentlessly. Moreover, those who come to lead others possess on the one hand a most tender heart which is pained at the slightest touch of other people’s misery, and on the other hand a determination to discharge their duties manfully, without being deflected from the right course under the mightiest pressure. Hence, though the Mother could be overwhelmed with sorrow, she could not be blinded by it for ever. Moreover it devolved on her in particular to arrange for the Shraddha (solemn obsequies) of grandmother on the eleventh day; for her brothers depended on her in such matters. As soon as the news reached Calcutta, Swami Saradananda made elaborate arrangements for the occasion; and the ceremony was well worthy of the great soul that had presented the Holy Mother to the world. Twenty-five brass pitchers, umbrellas, seats, sandals, and other things, were given away as gifts to brahmins. And the villagers, both brahmins and non-brahmins were sumptuously fed. The last wish of the grandmother was also fulfilled by cooking sufficient pumpkin curry for all.

The intense sorrow and the strain of the obsequies told on the Mother’s health heavily. As a result she became emaciated and she took one full month to recover. We do not know when she left for Calcutta after this. Most probably she did so some time in March or April, 1906. when she took residence again at 2/1 Baghbazar Street The venerable lady Gopaler Ma was then in her death-bed at the Nivedita School premises. When the Mother went to visit her a few days before she passed away, that very affectionate lady who looked upon all as her divine child Gopala, said, ‘Is it you Gopala come here? and she stretched forth her hand to take hold of something.

The Mother did not understand whom she meant and what she wanted. Then the woman devotee in attendance explained that she wanted the sacred dust of the Mother’s feet, who to her was none other than the Master as identified with her Gopala. The Mother had so long been revering Gopaler Ma as though she were her mother-in-law. But at that moment none cared to stand on formalities. The Mother made no objection, and the attendant took the dust of her feet with her apron and rubbed it all over the body of Gopaler Ma. With a heavy heart the Mother returned home. Gopaler Ma passed into eternal silence on the 24th of Ashadha (beginning of July), 1906.

The Mother returned to her native village before the Jagad-dhatri worship of 1907, which was celebrated with due solemnity in the presence of Brahmachari Krishnalal and others.

1. Rampriya Devi, first wife of uncle Prasanna.

Leave a reply