Life

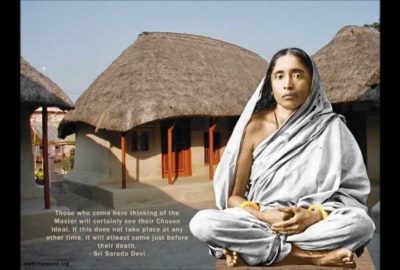

A LIGHT UNDER A BUSHEL

Whenever the Mother was at Kamarpukur or at Dakshineswar, she usually had with her either her mother-in-law, or the Bhairavi Brahmani, or her sister-in-law, or Hridaya, who regulated her movements in many ways. Hence, though her relation with the Master was most intimate, its outer expression had some extraneous influence imposed upon it. Now we shall study the divine relationship between the Master and the Mother unencumbered by any extraneous influence whatever. And yet in their free and sweet interchanges there was no meaningless sentimentalism, no mere emotional exuberance. In everything she did, the Mother was calm and collected without being lifeless, and bright and transparent without being blinding. It requires the closest attention to comprehend fully the different forms that the purity and modesty of the Mother took in the midst of this self-regulated freedom.

Apart from the few days that the Mother lived in the thatched house built by Shambhu Babu, she spent the rest of her Dakshineswar days in the small

Nahabat1. Those were extremely uncomfortable days; and the Mother, too, felt similarly. She said, ‘When I was at the Nahabat for serving the Master, in what discomfort I had to live in that small room, and what a lot of things lay huddled together there! Sometimes, I was all alone…Golap, Gaur-dasi and others stayed there now and then. Extremely small though the room was, yet in it were carried on cooking, sleeping, eating,—why, everything. Cooking was done for the Master, for often enough, he suffered from poor digestion, and the prasada of Kali did not suit him There was cooking for the devotees too. Latu was there; he came there having quarrelled with Ram Datta. The Master said, “ He is a fine boy; he will knead the dough for you.” There was no end to cooking, night or day. Ram Datta, for instance, came there and called out as soon as he alighted from the carriage, “ I shall take today gram

soup and chapati1” No sooner I heard this, than I started cooking here. There used to be chapatis made out of six to eight pounds of flour. Rakhal stayed here (with the Master); very often khichudi was cooked for him. Surendra Mitra used to pay ten rupees every month for the expenses of the devotees. Senior Gopal used to get things from the market.2 ..In the beginning my head would strike frequently against the doorframe as I entered the room; one day I even suffered a bad cut. But gradually I got used to it, and my head would bend as I approached the door. Fat women from Calcutta used to come to visit me, and standing at the doorway and holding the door-frame on either side with both hands, they would say, “Alas! In what a room our dear good lady is living—it’s like living in banishment ” ..I used to bathe at four in the morning. Whenever there was a little sunshine on the steps in the afternoon, I used to get my hair sunned. There was only one room on the ground floor of the Nahabat, and that was stacked with goods. Overhead were slings on which were hung potfuls of domestic titbits… The worst source of inconvenience was inadequacy of the facilities for bathing and personal cleanliness.1 Through forced confinement I developed physical trouble… And those fisherwomen were my companions. When they came for a bath in the Ganges, they kept their baskets on the verandah and went down for their dip. They talked a lot with me and took away their baskets when returning home. At night I heard the fishermen sing as they caught fish. ’

The Mother lived on the ground floor of the Nahabat and cooked below the staircase. She was too shy to come out during the daytime. Yogin-Ma thus described the Mother’s daily routine at the Nahabat: ‘Finishing her bath before four o’clock in the morning the Holy Mother sat for meditation; for the Master used to insist on meditation. Then she commenced her worship after finishing her other duties. The worship, japa (telling of beads), and meditation would take about an hour and a half. Then she sat for cooking under the staircase. When the cooking was over, if she got the opportunity, she would rub oil on the Master’s body with her own hands before his bath. The Master sat for his dinner between half past ten and eleven. Whenever he went for his bath, the Mother hurriedly prepared betel rolls for him as she kept on watching for his return. When he retuned, the Mother would spread a small carpet for him to

sit on for his meal, and keep ready a glass of drinking water. Then she would carry to him a plate of food. As he sat for his meal, she would converse on various topics just taking care lest his meal should be spoiled by any upsurge of spiritual emotion. None but the Mother could prevent such sudden upsurges during meal time. When the Master had finished eating, the Mother would hurriedly take something herself and drink a glass of water. Then she would make betel rolls. That over, she would sing in a low tone, and that very cautiously lest she should be overheard. Then when the mill blew the whistle at one o’clock, she sat down for her food, so that her lunch was never finished before half past one or two. After food she would take some nominal rest and then would sit down on the steps at about three for drying her hair. Then she would turn to trimming the lights and doing other odd bits of work, and then get ready for evening duties after somehow washing her body and clothes with the little water she kept in the Nahabat. When evening came, she would light the lamps and after waving the censer with the burning incense before the deities, sit for meditation. This was usually followed by cooking for the night, and the Mother would have her supper after all had finished. At last she would lie down after a little respite.’ Once, before dawn, when she was getting down the steps for a bath in the Ganges she almost trod on a crocodile which, taking alarm at the Mother’s approach, jumped into the river. Thenceforth, she never went for a bath without a lantern.

Numerous inconveniences and handicaps, heavy duties and troubles were there; but the Mother never really worried about them In later days, when casually alluding to all these troubles, she would sum up saying, ‘ Yet I knew no other suffering.. No discomfort could touch me if it was for his (Master’s) service. The day passed on joyously and quietly amidst everything.’ Some may fancy that there was nothing unusual in this her sense of joy. For was it not really good luck to live near the great Master, that fountain of bliss who drew large crowds to Dakshineswar, and whose sweet words charmed thousands into forgetting all the worries and anxieties of life in his presence? This attitude may appeal to those who do not care to look at the matter more deeply. But how many in real life feel that kind of attraction for the Master even after knowing so much of his greatness? How many even during his life did so, and how many among those who felt that love stayed on at Dakshineswar? We have also to remember that the Holy Mother whose life revolved round the Master alone, had seldom even a distant view of him. She said, ‘Sometimes even during as long a period as two months, I couldn’t see him even once. I composed myself by saying “O mind, what merit have you earned that you will get his darshan (sight) every day?” Standing erect (behind the screen of plaited bamboo chips, with which the verandah of the Nahabat was surrounded), I used to hear the lines that he sometimes added extempore to the kirtana songs. This produced rheumatism.’ Would but one stop to consider for a while the absolute purity of heart and incomparable love that are necessary for standing long hours behind a screen, just for the sake of having an incomplete glimpse of the Master through a hole and deriving pleasure thereby! Though the Mother was then physically separated from the Master, her heart ever hovered around him. The number of devotees visiting the Master at that time was quite considerable, and throughout the day and till late into the night there was a continuous flow of music solo or choral, dancing, and ecstatic moods. The Mother saw and heard these and thought within herself, ‘If but I were one of the devotees over there, I would then be ever so near the Master, and would hear so many things!’ Here on one side is the new Incarnation giving free and varied expression to his message for the age, and on the other side is the Mother of the Universe keeping herself under the voluntary restraints of a monotonous life;

on the one side is sparkling disport and on the other eager gazing—this is altogether a rare phenomenon! Those days might have had their ups and downs. Near as she was, she was still very far; and yet in the memory of the Holy Mother the troubles and tribulations of those days were obliterated as she looked back lingeringly at the bliss that suffused her life as a whole in spite of all impediments; and she said, ‘In what bliss I was! What a curiously mixed crowd of people came to see him then! Dakshineswar used then to be a mart of

The Master was not, of course, unmindful of her comforts; on the contrary he tried to keep her happy in every way. He called that little room a cage, surrounded as it was by bamboo chips. Lakshmi Devi, his niece, too, often stayed there. The Master called them in fun a pair of parrots. When Mother Kali’s prasada was sent from the temple to the Master’s room, he said to his nephew Ramlal, ‘Hullo! There is that pair of parrots in the cage. Carry to them some gram and fruits.’ New comers naturally thought that there were some real birds; even Master Mahashaya1 laboured long under that wrong impression. When Lakshmi Devi was not there, the thought of the rheumatism and loneliness of the Holy Mother worried the Master very much. He said to her, ‘If a wild bird lives in a cage it becomes rheumatic; you should go out now and then to have a stroll in the neighbourhood.’ He did not stop with this. When visitors had left the temple premises at noon, he would go to her and ask her to walk out through the backdoor to spend some time with the wife of one Sri Pandye. The Mother used to return after the evening services when the Panchavati side became quiet again.

Sometimes the Master created funny situations as though to impress on others the unique intimacy of the relationship that he had with the Mother. Once when a discussion arose whether the Master or a certain devotee had a fairer skin, the Master appointed the Mother as the umpire. He told her that she would have to watch them and formulate her opinion as they walked by the Nahabat northward of the Panchavati. The Master’s colour was at that time fair and bright like pure gold and could hardly be distinguished from the gold amulet on his arm. Yet, the Mother, an impartial judge, pronounced her verdict in favour of his rival.

In fact, the current of love of this divine couple was equally strong at either bank; the Master was as warmly attached to the Mother as she was to him Gauri-Ma once said, ‘Though these two sometimes did not see each other for six months together, in spite of being only about seventy-five feet apart, how deep indeed was their love for each other!’ Once when the Mother had a headache the Master felt extremely anxious and went on asking Ramlal again and again: ‘O Ramlal, why does that headache trouble her?’

The Master saw to it that the Mother was not needlessly overburdened with work, busy as she was the whole day. Once, while on a walk with Rakhal in the garden of Beni Pal of Sinthi, he came across some ghosts who implored him to leave the garden, as the holy atmosphere he diffused around him was too strong for them to bear. It had been arranged earlier that he would spend the night in the garden; but the importunity of the spirits made him change the plan at once.

He called a carriage and returned to the temple premises at dead of night when the gate was closed. He got it opened and walked in. The Mother, whose mind was ever eager for any opportunity of service to him, got up at the sound of his steps and said to the maidservant, ‘O Jadu’s-mother, how shall we manage?’ They were talking in the Nahabat; but the Master’s careful ears caught the sound. He sized up the situation at once and said, ‘Don’t you worry, my dears, we have had our meals already.’

The question of the Mother’s maintenance after his passing away was also present in his mind. Though detachment from worldly affairs was a point of faith with him, he asked the

Mother, ‘How much money would you require for your personal needs?’ The Mother replied, ‘I can manage it with, say, five or six rupees.’ Then he inquired, ‘How many chapatis do you eat in the evening?’ The Mother blushed at this personal question and hung her head in shame without answering. But the Master went on repeating his question and she had to reply at last, ‘Say, five or six.’ On that basis the Master calculated and said, ‘Then it’ll be quite enough if you have five or six hundred rupees.’ Afterwards he deposited that amount of money with

Balaram Babu1 who invested it in his own estate and sent her thirty rupees every half year as the accruing income.

It is a wonder to think how a god-intoxicated soul like the Master could keep his attention fixed on so many things. Adored as God by devotees who were ever at his beck and call, he could never be unmindful of her prestige and independence. As for his courtesy towards the Mother, we get an attestation from her own words: ‘I was fortunate to be wedded to a husband who never addressed me as thou (tui). The Master never hurt me even with a flower, never called me “thou” in place of “you”

(tumi).’2 One day the Mother carried to the Master’s room his scanty dishes consisting of very thin pieces of cake (made by spreading liquid flour on a flat frying pan) and soojee (semolina) porridge. As she was leaving the room after placing the dishes at the proper place, the Master thought it was his niece Lakshmi and called out, ‘Mind, thou (tui) shuttest the door. ’ The Mother said, ‘Yes, here I close it.’ Recognizing the Mother’s voice, he became greatly embarrassed and apologized, ‘Ah, it’s you ! I thought it was Lakshmi. Don’t you mind this.’ Nay, that unintentional disrespect upset him so much that the very next morning he went to the Mother’s door and said, ‘Look here, my dear, I had no sleep last night, because of brooding over my rudeness to you. ’ As an illustration of the honour in which the Holy Mother was held by the Master who regarded all women as the veritable manifestation of the Mother of the Universe, he told the devotees that he saluted the Mother after she had rubbed his feet with her hands. On another occasion he said, ‘I wanted to go to a a certain place. When Ramlal’s aunt (the Mother) was consulted she forbade me; so I gave up the idea. ’

Though the Master thus honoured the Mother and treated her with utmost consideration, he knew that there was a wide difference between them in age and experience. Moreover, there was none else to instruct the Mother either about worldly matters or about spiritual practices. So he himself gladly shouldered the duty. For instance, he said to the Mother, ‘One has to work; women should not sit idle, for if one sits idle, many vain thoughts, nay evil ideas, may crop up.’ The Mother once said, ‘He brought me some raw jute and said, “ Twist this and make slings for me; I shall keep (in them) sweets, etc., for the boys.” I twisted it into strings and made slings; and with the waste fibres and a piece of thick cloth I made a pillow. I used to spread a coarse mat over a piece of hessian and put that pillow under my head. I slept as soundly on those things as I do now on these (cots, etc.,)—I don’t find any difference, my child!’

In fact, owing to her own nature and the teaching of the Master, she followed his instruction, ‘Adapt yourself to time, space, and person,’ so perfectly, that

even the Master once said to Hridaya in wonder: ‘O Hridu, I had great apprehension, lest she, a village girl, should, by her rustic behaviour incur public criticism and put us to shame. But as to that she is so cautious that nobody knows her movements; even I never saw her going out.’ The Master undoubtedly meant this as a compliment. But the Mother became very much worried, thinking, ‘Ah me! The Mother of the Universe actualizes for him whatever idea crosses his mind; and now, methinks, I shall catch his eyes whenever I go out.’ To avert this she prayed, ‘O Mother, kindly protect my modesty.’ That prayer was so fully granted that though she lived at

Dakshineswar for a long time, she escaped public gaze so completely that the cashier of the temple, the chief resident officer, when asked about her said once, ‘I have heard that she is here; but I have never seen her. ’

Though the Mother was very shy and effaced herself completely, subduing herself to the will of the Master, yet in one respect she maintained her independence and that was in the domain of her motherhood. Of this we shall have many instances; for the present we shall deal with three only. The Mother had not many companions then; the fisherwomen came frequently; a maid-servant too was there for some time; and at times there would be a few women visitors from

Calcutta. The number of devotees was not very large. At that time there used to come to her an old woman who had lived a somewhat loose life in her youth; but now like a devotee she prayed to the Lord and came often alone to the Mother who talked in a friendly spirit. Noticing this, the Master said one day, ‘Why is that woman here?’ The Mother expostulated, ‘She talks now only of Hari. What’s the harm in that?’ The Mother knew that human nature changes, that even evil characters repent and become good. On the other hand, the Master’s sense of duty warned him that the Holy Mother should be protected from the company of persons who might come with impure motives. Besides, intimacy with such undesirable people might rouse adverse criticism from worldly-minded visitors. So he said with disdain, ‘Pooh, pooh! a public woman! To think of chatting with her, whatever the extenuating factors! What a nasty idea!’ The Mother certainly understood the need for caution. Whatever might have been her past, she now trod the path of virtue and looked upon the Holy Mother as her own mother. How could the Holy Mother then drive away one who wanted to be comforted—the Mother whose life was to be a solace to thousands of sinners and spiritual wanderers? And all that cruelty she was to show for the sake of mere social propriety! The conversations, therefore, went on as before even after the Master’s observation. The Master too, intuitively understanding the Mother’s feeling, did not refer to the matter again.

Subsequently, when visitors became more numerous and fruits and sweets and other offerings were placed at the feet of the Master in plenty, he used to send these to the Nahabat. It was found, however, that apart from the little that was needed for the Master, the Mother did not care to retain them, but gave them away freely to the women and young devotees and the children of the neighbourhood who came to her. Her mother’s heart would not allow her to send away any visitor or devotee without giving him or her some fruit or sweet. In this she was liberal to a fault. One day when she had thus used up everything, Gopal’s Mother1 cried out, ‘My dear daughter-in-law, why have you not reserved anything for my Gopal!’ The Mother hung her head in shame. Just then Navagopal Babu’s wife alighted from a carriage and handed over to her some sweets and saved the situation. The Mother did not learn her lesson still, or perhaps it was impossible for her to change her nature. The Master too knew of this extravagance, and just because he knew he argued with her one day in his room, ‘How can it be managed if there is such extravagance?’ At this the Mother quietly turned her back and walked away to the Nahabat. The Master now was in a quandary and said to his nephew, Ramlal, ‘Hullo Ramlal, go and pacify your aunt. If she gets angry, everything will be undone with this (pointing to his body).’ This was a voluntary defeat of the Master before the blossoming motherhood of Sarada Devi.

The Mother was one day recounting the memories of those old days to Yogin-Ma and others, when Yogjn-Ma suddenly inquired why the Mother seemed to be so wilful in certain matters, even against the Master’s advice. The Mother said with a smile, ‘As for that, Yogen (Yogjn-Ma), can any one obey another in everything?’ And she added after a little reflection, ‘Well, my dear, whatever you may say, I shan’t be able to turn away anybody if he addresses me as Mother.’ One day, she made this abundantly clear to the Master himself. In this last incident there is not only an example of selfless service at its highest, but it is also full of the fragrance of motherhood in its first bloom As the Mother felt too shy to come into the Master’s room in the presence of others, the room was cleared of people at night to enable her to serve the Master his food. One night, when she had just stepped on to the verandah of the Master’s room, a woman devotee suddenly came up and snatched away the plate of food saying, ‘Give it to me, Mother, give it to me!’ The woman placed the plate before the Master and left as quickly. The Master sat down for his meal; the Mother too sat by him But he could not touch the food and said looking at the Mother, ‘What’s this you have done? Why did you give it into her hands? Don’t you know her? She is immoral. How can I now eat what has been defiled by her?’ ‘I know all that,’ said the Mother, ‘but do please take this tonight.’ The Master would not still touch it, but at the Mother’s importunity said, ‘Promise that you won’t hand it over to anybody else hereafter.’ With folded hands the Mother replied, ‘That I cannot, Master! I shall certainly bring your food myself, but if any one begs me by calling me “Mother”, I shan’t be able to contain myself. Besides, you are not my Master alone, you are for all.’ That cheered up the Master and he began eating.

1. The Nahabat is a two-storeyed brick structure, about 75 ft. north of the Master’s room. It is on the Ganges, on the way to the Panchavati where the Master used to meditate. The room downstairs is octagonal in shape, each wall measuring 3’ 3* inside and the maximum distance between the walls across the floor being 7’ 9*. The floor area is a little less than 50 sft. Round the room is a verandha 4’3” in width more or less. The only opening, a door on the southern side, measure 4’ 2”x2’ 2”. On the eastern side of the verandha is the staircase leading upstairs. Under this the Mother had her kitchen. During the Mother’s stay, the verandah was surrounded by a thin screen of plaited bamboo chips.

1. Indian bread made of wheat flour flattened into round discs and baked in fire.

2. Of the persons mentioned here Golap (or Golap-Ma) and Gaur-dasi (or Gauri-Ma) were women devotees of the Master, the former afterwards becoming a constant companion of the Mother. Latu, Rakhal, and Senior Gopal (or Gopal-dada) renounced the world, assuming the names Swami Adbhutananda, Swami Brahmananda, and Swami Advaitananda. The last named was older even than the Master and hence had the epithet ‘Senior’. The rest were all lay disciples.

1. There was no bath-room. When Yogin-Ma, a woman devotee of the Master and later a constant companion of the Mother, visited Dakshineswar, she noticed all this and took up the matter with the others. As a result there was some minor improvement.

1. Mahendranath Gupta, the writer of the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna in Bengali. As he was a teacher in a High School, the devotees called him Master. Mahashaya means a dignified man, and is equivalent to ‘ Mr ‘.

1. A staunch devotee of the Master and one of his rasad-dars (suppliers of needs), who lived in Calcutta but had estates in Orissa.

2. In Bengali tui (thou, Hindi tu) is used for addressing inferiors or little ones, tumi (you, Hindi tum) for friends, equals, parents, brothers, sisters etc; and apani (Hindi ap) for respected persons.

1. An old lady disciple of the Master, who worshipped Krishna in His form of a little child. At the end of her long practice she was blessed with a constant vision of the Divine Child whom she subsequently identified with the Master. The Mother thus became her daughter-in-law.

Leave a reply